While Theravadin Buddhism does not itself have a yoga of sleep or dreaming, it is a dream yoga in the broader sense, that is, a methodology for waking up out of sleeping, dreaming, and sleepwalking through life. Like IDL, it places emphasis on awakening from our waking delusions, in the belief that it is the consciousness of the waking state that determines out consciousness in other states. In addition, Theravadin Buddhism lays important conceptual foundations that not only differentiate it and Tibetan Buddhism from Hinduism, but provide the foundation for Tibetan dream yogas.

Similarities of Buddhism to Hinduism

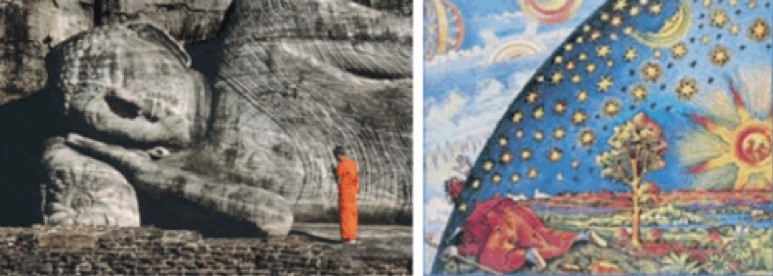

Originally spread throughout the Indian subcontinent, since the Islamic invasion Theravadin Buddhism has traditionally been found only in Ceylon and southeast Asia, but now has a worldwide following of at least 150 million. Like Hinduism, Theravadin Buddhism, predating Mahayana and Tibetan traditions, believes that life is delusional, like a dream, and that a yoga is needed to wake up out of it. Buddha subscribed to a narrow definition of yoga. He said, “To enjoy good health, to bring true happiness to one’s family, to bring peace to all, one must first discipline and control one’s own mind. If a man can control his mind he can find the way to enlightenment, and all wisdom and virtue will naturally come to him.” Gautama wasn’t focused on improving society; instead he emphasized the creation of monastic communities of people who sought personal liberation. These people would in turn improve society. “The teachings of the Buddha created hope and aspiration for those who otherwise had no hope of salvation and freedom of choice in a society that was dominated by caste system, predominance of ritual form of worship and the exclusive status of the privileged classes which the Vedic religion upheld as inviolable and indisputable.”

To understand Buddhism it is important to understand the consciousness of its founder, Siddhartha Gautama, a prince in northeastern India in the fifth century BCE. His contributions need to be understood within the context not only of Indian culture but the suppositions of the religious traditions in which he was immersed and participated. These were thoroughly Hindu, but because of the many diverse margas and darshanas within it, it may be assumed that Gautama was exposed to many conflicting points of view. There is very little in the teachings of Gautama that is not compatible with this or that school of Hinduism, so much so that it coexisted in India with Hinduism until the Moslem invasion in 664 AD. However, there is evidence that his ethical teachings came from outside the mainstream Brahmanical Hindu culture at that time and are associated with the pre-Aryan Aramaa.[1]

Both Hinduism and Buddhism believe in samsara, karma, and reincarnation, compassion and non-violence toward all living things, and ignorance as the source of suffering. Both also believe in the practice of meditation, concentration, and the cultivation of certain states of mind (bhavas), detachment and renunciation of worldly life as a precondition to enter spiritual life, and liberation, not rebirth or heavenly life, as the solution to suffering. These notably non-shamanistic concepts and beliefs co-exist within a remarkably shamanistic cosmology: the existence of several hells and heavens, and the existence of gods or deities on different planes, for which Hinduism and Buddhism use similar names, such as Indra, Brahman, and Yama. In particular, they share a four-tiered cosmology: Both religions recognize the earth as center of the universe, resting on the mountain Meru, surrounded by seven concentric rings of mountains with the hells of Asuras below and the worlds of devas above. The Hindu version contains a subterranean world, the Earth, a mid-region populated by celestial beings, the heaven of Indra, and the world of Brahman. The Buddhist version is different, but the region populated by celestial beings in Hinduism is populated by devas who inhabit worlds of passions and desires. The “heaven of Indra” is not much different, comprised of more devas that are inhabiting the worlds of form and perception. The Hindu world of Brahman is call Brahma lokas and is inhabited by great beings. The microcosm and macrocosm mutually reflect, in that the whole cosmos is represented in the inner world of a human being.

What we can conclude then is that both Buddhism and Hinduism share a combination of a belief in the reality of realms that shamans, channelers, mediums, and most contemporary monotheists and new agers could agree upon in broad outline, if not in particular details. The mystery of how and why a naively realistic and concrete view of reality not only managed to survive within Hinduism and Buddhism, but up until the current day, among well-educated and experienced exponents of personal development, is a topic for later chapters.

Characteristics Unique to Buddhism

Hinduism was not founded by any one individual, as was Buddhism. Hinduism believes that the Vedas are divine revelation and Hindus attempt to justify their decisions and choices in terms of them. Buddhism does not believe in any Hindu scripture, but some followers venerate and take as truth various Buddhist scriptures in the same way that Hindus do their own. While Hindus believe in an individual imperishable soul, atman, as well as God, Brahman, Buddhism believes in neither. Hinduism views Buddha as an incarnation of Vishnu, but Buddhists do not accept any Hindu god either as an equal or as a superior to Buddha. Theravadin Buddhists do not worship images of the Buddha or any gods, including the Mahayana Buddhist concept of Bodhisattvas. Theravadin Buddhism considers Buddha the supreme being and worships him with images. Hinduism recognizes as main aims of life religious duty (dharma), wealth, (artha), pleasure (kama), and liberation (moksha). Because Buddhism considers the world as full of suffering it recognizes only two practices, Buddha’s teachings, dharma), and liberation, nirvana. Buddhism does not believe in the four ashramas that define the Hindu caste system and exclude no one from monastic life due to caste. While Hinduism may be practiced by sects with different beliefs, its path to salvation is essentially an individual practice. Buddhism is traditionally practiced by groups of monks in monasteries, supported by the surrounding laity, who accumulate good karma by serving them and sending their children there. Buddhism requires refuge in the “three jewels” of Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha; Hinduism provides broader options. Yoga has a much broader connotation in Hinduism than in Theravadin Buddhism. While all yogas in Hinduism aim to achieve liberation through union of the soul with God, in Buddhism, meditation is meant to suppress changes in the self and its formation, resulting in the elimination of its existence. The result for both is the cessation of all desires; for Buddhism that experience is conceptualized and experienced as sunyata, emptiness, while for Hinduism it is self-realization as Atman unified with Brahman.

Two Theories of Truth and Integral Deep Listening

While the idea that different standards, rules, and behaviors apply to Heaven and Earth and the unconditioned and conditioned realities, nirvana and samsara, are widely and commonly found in human conceptions of reality, it is perhaps most clearly enunciated by Mahayana, but already existed in Theravadin Buddhism.[2] The two theories of truth show up in the distinction between real and delusional states, with life being dreamlike and liberation defined as freedom from delusion. Generally, the past, internal, subjective, emotional, evil, and chaotic are considered to be delusional and unreal while the present, external, objective, rational, good, and peaceful are considerd to be true and real. We have seen that it also shows up in Indian dream interpretation as the distinction between secular, mundane, and meaningless dreams and spiritual, inspirational, and transformative dreams. It can also be observed in Hinduism as the distinction between purity and impurity, as rajas, sattvas, and tamas foods and occupations.

IDL does not recognize two realms of delusion and reality, dream and enlightenment. Instead it believes these are conditional states subject to the perspective which is taken, and that what was taken to be absolutely Real and True is found to be conditional and conditioned once that perspective is internalized. IDL considers the Two Truths Doctrine to be a holdover from shamanism and an unhelpful codification of dualism that generates a spiritual Darwinism that separates the sheep from the goats, the elect from the damned, the Pharisees and Sadducees on the one hand from the unclean on the other, and the Chosen People from the goyim. While Darwinism is survival of the fittest, neo-Darwinism is the belief that the rich deserve what they have because they are more fit and the poor and unfortunate deserve what they have because they are less fit. Spiritual Darwinism puts spirit in competition with form, life, matter, sensory experience, emotions, and thinking.

The Two Truths Doctrine is largely responsible for generating the fundamental delusion of exceptionalism: grandiosity writ large on the stage of community, nation, and the global community. As such, it is the root of untold misery. The shamanistic roots of the Two Truths Doctrine have been laid out above in the chapter on shamanism. It reflects a dualism that shamans, Manicheists, Zoroastrians, Mithrians, Jesus, and monotheists of almost all persuasions could appreciate.[3] Besides the obvious discriminatory problem built into dualisms, they have nothing to do with unitary mystical states, and particularly not the non-dual. The fact that the world looks unitary from a non-dual state and dualistic from a mental state does not validate a dualistic worldview. The latter is an artifact of the self remaining identified with mind; the former is the worldview of someone who has learned to look at both the non-dual and the dualist world of form from the perspective of non-discrimination. While such a view does not indicate that a person has evolved into the transpersonal levels, it is probably an indication that they have achieved multi-perspectival vision-logic on at least the cognitive level. However, if a person has experiences of mystical union and claims to be a psychic, guru, llama, saint, or sage, and still believes in the Two Truth Doctrine, it is a reason for caution. In fact, expression of belief in a dualism is a telltail sign that you are dealing with someone or something that is at a personal level of development, at best, and probably below, because most people at personal levels of development are not attracted to spiritual dualisms because they look too much like superstition and concrete naïve realism. The problem is that when you create a non-dualistic reality you thereby create a dualism between non-dualism and dualism. Sunyata, or emptiness, is an attempt to heal this split by equating samsara and nirvana, Buddhists still uphold the Two Truths Doctrine. IDL may be wrong about this because some very intelligent and advanced mystics, Nagarjuna, for example, accept the Two Truth Doctrine.[4] The Two Truths Doctrine is found in most, if not all, the sacred traditions of the world.

Integral Deep Listening strengthens dream yogas is by providing a method that experientially demonstrates the non-reality of the Two Truths Doctrine. It does so by putting you in touch with perspectives that are legitimate and authoritative, and yet do not make these distinctions and have no use for them. You will find for yourself that interviewed toothbrushes and shoes are no less sacred, pure, true, or real than interviewed angels, bodhisattvas, and beatific deities. More importantly, you will find that they themselves do not discriminate between Truth and Reality, on the one hand, and falsity and delusion, on the other, in any absolute sense. However, they very much differentiate among degrees of truth and falsity, reality and delusion. By repeatedly becoming such perspectives you will learn to see the world independently of this basic dualism; you wil learn to stop evaluating yourself and your experience with others, dreams, and meditation in terms of it. The consequence is the reduction of a fundamental cognitive filter that blocks transpersonal development.

Integral Deep Listening sees dualistic perception and cognition as a necessary, vital, and useful tool for development because discrimination is the fundamental process by which the mind grasps and works with reality. Therefore, dualism is necessary for feeling, forming preferences, and thinking. To say that dualism is “bad,” or “wrong,” or “unnecessary,” is to say that emotions, preferences, and thinking are these things. However, making distinctions is not the same as dividing reality into two different categories. You can use dualism as a tool to make distinctions and still not divide reality into categories. This is the path IDL takes, and it does it not primarily for philosophical or psychological reasons, but because interviewed emerging potentials generally do not do so, particularly not the ones that score high in the six core qualities.

People need such a tool to outgrow the Two Truths Doctrine. There are too many brilliant, dedicated seekers throughout history who have remained in it to allow us to believe that reason or experience in meditation will naturally cause people to outgrow it. IDL thinks that this tenacious remnant of shamanistic consciousness will persist unless you have some tool like IDL that allows you to get in touch with respected perspectives that do not use it.

This is a core benefit of Integral Deep Listening that you will not and cannot outgrow. As long as you are alive, it will continue to access perspectives that are less dualistically-immersed than you are, regardless of your level of practice. It will also routinely remind you of just how deluded you are, regardless of what you think of your progress or what those around you may think you are. This is important, because while it is theoretically possible to be too humble and too selfless, it is difficult to imagine circumstances in which more is not better, as long as humility and selflessness exist within the context of strengthening and balancing the six core processes and qualities.

Samsara: Life is Dreamlike in its Illusoriness

The Buddha said, “The world, indeed, is like a dream and the treasures of the world are an alluring mirage! Like the apparent distances in a picture, things have no reality in themselves, but they are like heat haze.”

“In the sky, there is no distinction of east and west; people create distinctions out of their own minds and then believe them to be true.”

Within Buddhism, samsara is defined as the continual repetitive cycle of birth and death that arises from ordinary beings grasping and fixating on a self and experiences. This is essentially the Hindu definition of samsara, meaning that Buddhism, like Hinduism, views earthly experience as intrinsically a result of grasping and self-fixation. This is important to remember, as you will find many current-day apologists for Buddhism who want to reinterpret the message as one that says something different. For example, “Buddhism does not see the world itself as an illusion, but the emotions and concepts we hold which provoke our responses to the world are seen as the illusion.” While Buddhism can be interpreted in such a way, this is not the way Buddhism has historically interpreted itself. This issue is important for those who have an investment in protecting Buddhism from criticisms that it is life-denying. However, Integral Deep Listening does not have any need to have Buddhism (or any tradition) say one thing and not another. This is the tendency of all True Believers in any age: to read their value system into scripture.

IDL does not view life as intrinsically delusional or as samsara. Delusion is caused by the physical, emotional, and mental filters that we have evolved as adaptive advantages for life. These filters have important and deep-seated purposes; they are not going to go away just because we suddenly realize they are there. It often takes drug hallucinations, mystical experiences, or near-death encounters to drop at least some of them. The most entrenched seem to be the perceptual cognitive distortions associated with our level of self development because it is carried into dreaming, lucid dreaming, mystical and near death experiences. We can drop our bodies and time-space-causal filters, but we will continue to interpret events in terms of our current level of development. This is why we need to evolve and thin the self; it is the weaver of the web of samsara, a brilliant insight that the Buddha understood, which was a new development in world religion and philosophy. Most of the world has not understood it yet, much less recognized its importance for waking up.

Avidya (Ignorance), the Source of Samsara

For Buddhism, samsara arises out of avidya (ignorance) and is characterized by dukkha (suffering, anxiety, dissatisfaction). It is ignorance that causes craving. In the Buddhist view, liberation from samsara is possible by following the Eightfold Noble Path, which personifies wisdom. As with Hinduism, which has a similar emphasis on wisdom, Buddhism commits to the primacy of one of the six core qualities, which means that the other five are placed either in supportive roles or are subsumed into wisdom as “facets” of it. Notice that either move can be made with any of the six core qualities. Christianity tends to do so with love/compassion; shamanism with confidence; mysticism with witnessing; Chinese traditions with peace as a response to chaos. Integral Deep Listening believes a wiser solution is to note that all are interdependently co-originated, meaning that they are equally essential to enlightenment. While Buddhism rightly acknowledges this concept, it does not methodically follow its implications and see that the cause of suffering involves imbalances among multiple core values.

The implication of an interdependent approach such as IDL uses is that suffering is a consequence of both an absence of and imbalance among the six core qualities. Ignorance is the absence of one core quality, wisdom. Each of the other five core qualities has a corresponding deficit, each of which plays an equally important role in the generation of suffering and samsara. These are fear, selfishness, attachment, stress, limitation, and subjective filtering, deficiencies that are associated with the absence of confidence, compassion, acceptance, inner peace, and witnessing. It is not only important to recognize the co-originating nature of suffering associated with all six of these qualities, but to recognize that reducing some but not the others does not end suffering. For example, you can become very wise and still be selfish. You can be wise and attached to your wisdom You can be wise and subjectively identified with your world view. All of these factors need to be used in tandem to leverage you out of the others. This is what is meant by balance. You will grow much faster if you have a number of different causes and solutions, because you then have more tools in your toolkit, more options for response, and greater adaptability.

While Buddhism sees ignorance as the cause of samsara, IDL views it not only as a consequence of a lack of balance in the six core qualities but as identification with the filters which generate our identity and sense of self. This is because samsara is caused by identification with these filters, called skandhas in Buddhism, which create the core illusion of self. The goal is not to eliminate the self but to eliminate identification with the self and the filters that generate delusion. You do not have to actually eliminate the delusion, just like you don’t have to stop the sun from rising to stop the delusion of geocentrism.

The Wheel of Karma

The Buddhist concept of karma is very similar to that found in Hinduism, with the exception that it is driven by an illusory self: “Our karma producing actions are caused by the delusion that we are real selves, that the ego is a permanent identity; therefore this self is dominated by egotistical desires or attachments. It is desire, passionate attachment or repulsion and hate, caused by ignorance as to the truth about the non-existence of the self that shackles us to the wheel of samsara – rebirth. Therefore, the key to the release from this wheel is the understanding that there is no self or ego and consequently that desires and the satisfaction of them are the illusory products of ignorance.”

If there is no self, then what is it that accumulates and carries on karma from one existence to another? What is the relationship of this to the nature of ultimate reality? Theravadin schools accepted the existence of elements and aggregates to explain what reincarnated. Elements are called dharmas: sensation, form, memory, space, and energy. Aggregates are called skandhas: material form, sensation, ideas, concepts, and understanding. Salvation is attained by insight, or enlightenment, concerning the truth that self is merely a temporary association of these dharmas and skandhas.

Karma is one way to understand the influence of causation of humans; it is neither the only way nor is it the best way, because it causes people to stay attached to exactly that sense of self that Buddhism claims does not exist. This is because it promotes the concept of personal causation and therefore not only overpromotes responsibility for causation, but by implication, the reality of the source of that causation, although the reality of that source is denied in Buddhism. Instead, IDL views whatever happens not in terms of cause and effect or karma, but as a wake up call. The first model emphasizes responsibility; the second model emphasizes enhanced awareness that leads to improved behavior. Isn’t that the point?

Integral Deep Listening sees the concept of karma having important individual and societal purposes, motivating people to obey, do well, be ethical, and believe that there will be eventual rewards for right actions. It also had the very practical result of the laity maintaining monasteries by bringing food and donations in order to attain “good merit,” or positive karma, which would result in a better rebirth. IDL teaches the taking of responsibility through identification with multiple perspectives. It is exactly because IDL is so effective at showing people themselves in a way that they take responsibility for it, that many people will not do it. If I want to make excuses for myself or avoid responsibility, why in the world would I do something that pointed out to me that was exactly what I was doing? Every interview asks, “What aspect of this person do you most closely personify?” Clearly, there is not only an encouragement of ownership but a thoughtful consideration of the implications of such ownership. Therefore, IDL encourages the taking of responsibility just as the doctrine of karma encourages. However, by not using the concept itself, IDL avoids the multiple problems that it inevitably raises, including predestination, predetermination, determination, fate, social and cultural coercion, and discrimination due to karma.

Integral Deep Listening does not view karma as a characteristic of the natural world as Hinduism and Buddhism does. Following Kant, it sees time, space, and causation as categories that the mind intrinsically uses to make sense of the world rather than objective realities. This is not to say that causation is not a reality for humans; it is. However, causation is not a characteristic of life, but of human consciousness. Consequences are brought about by fear, guilt, conscience, the choices of others, and natural laws, like gravity. Integral Deep Listening also does not recognize a law of karma because few interviewed emerging potentials need it or use it.

We have to outgrow the assumption that making karma irrelevant, completely apart from debates over its truth or not, will result in an unlawful, unregulated life in which one is free to do whatever they want, or that the only ideological option to karma is materialism. Most interviewed emerging potentials do not subscribe to either viewpoint, indicating that there are other possibilities. IDL is fully aware that you are not going to change your beliefs based on anything you read here, nor should you. Instead, it invites you to look at the perspectives of your own interviewed emerging potentials and draw your own conclusions.

Freedom from Rebirth

Once you accept karma, you are on a path to crazy conclusions. One is that the “effects” of your karma must land you in different places, since different causes have different effects. These places then have to be created, or at least hypothesized. Such is the case with Buddhism. We have seen that it believes in the existence of five realms or six, depending on who you ask, for you to transmigrate or reincarnate into. You may end up as a Naraka being that lives in one of many Narkas, or hells. The implication, as in all religions with hells, is that you will be appropriately scared of that possibility and therefore behave in such a way that you don’t end up there. If you aren’t quite so bad, but aren’t particularly good, you will simply become a ghost, called a Preta, sharing space with humans, but considered another type of life. Instead of a ghost, you could reincarnate as an animal, where there are various learning opportunities. This is better than being a ghost, because at least you are alive, even if an animal, because earthly existence provides opportunities for creating good karma that being a ghost doesn’t. Notice that Buddhists and Hindus differ with most reincarnation-believing Westerners on this, who generally consider being a ghost to be a higher developmental state than incarnating as an animal. What is good and important about incarnating as a human is that it is one of the realms of rebirth in which attaining Nirvana is possible. You can use it to escape the wheel of karma and rebirth. Notice that what this does is define the entirety of life in terms of its instrumentality; instead of being a good in itself, its value is as a launching pad to get somewhere else. Wise Buddhists understand that this is a contradiction with what they know: that there is nowhere to go and that escapism to some imagined preferred state of existence keeps you stuck in suffering. Knowing this, why did Buddhism not jettison karma and reincarnation? As we have noted above, one reason is that it allowed the monastic system to exist. Without the laity accumulating good karma, with the reward of a better rebirth, by contributing support, how would the teaching centers be sustained? This is an example of how functionality in the external collective social quadrant creates interpretations in the interior collective quadrant that slow down and impede the expansion of consciousness in the interior individual quadrant.

Beyond human incarnation you have the opportunity to be reborn as a god, deity, spirit, or angel, called Devas. These have even a higher likelihood of accessing Nirvana than humans do. The Mahayana Buddhists add another possibility, after humans and before Devas, called Asuras. These are lower deities titans, and interestingly, powerful but negative forces, such as demons and antigods. It is another interesting metaphysical twist that some evil forces are closer to attaining Nirvana than say, advanced Buddhist meditators. This may be a concession to the human experience that there are forces that cause floods, disease, and death that are positively harmful but must be respected because they are part of a larger cosmic order. Such an awareness sets up a psychology that naturally leads to a need to appease such forces with offerings, confessions, and sacrifices, reinforcing a shamanistic worldview that underpins almost all world spiritual traditions. The above are further subdivided into thirty-one planes of existence. Rebirths in some of the higher heavens, known as the Suddhavasa worlds or Pure Abodes, can be attained only by skilled Buddhist practitioners known as anagamis, non-returners. Rebirths in the arupa-dhatu (formless realms) can be attained by only those who can meditate on the arupajhanas, the highest object of meditation. While East Asian and Tibetan Buddhism add intermediate states, bardos, between one life and the next, Theravadin Buddhism rejects this; you go immediately to the existence that your karma has earned you after you die.

Integral Deep Listening views all this as prepersonal mythology that naturally and consistently arises out of the basic premise that karma exists and the naïve realism that produces the shamanic three-tiered cosmology. While educated Buddhists may distance themselves from such beliefs, they do not denouce them, imagining that they are “necessary” for the laity and those at earlier stages of development. The consequence is that they perpetuate a cultural context that keeps people stuck at prepersonal levels of belief.

If you buy the premise that what you experience in your dreams, trance states, and near death experiences is real, and that karma exists, then these levels and realms become reasonable. Pretty soon you are believing the realms of gods and deities of the solar system, galaxies, and galactic clusters enumerated in authoritative works like The Urantia Book. The only escape from the crazy implications of such crazy conclusions is to not buy the premises. Is what you see in your dreams and trance experiences really “real,” or could it be a product of your culture and level of development? Is it true that there is a “you” that gets rewarded or punished based on your actions? Buddhism should be able to avoid this, since it does away with an immortal, eternal self or soul. However, it is so wedded to the dogma of karma that it cannot. Instead of an emphasis on causation, which hundreds of years later Nagarjuna would show is itself subject to the same demolition as the concept of the self, Integral Deep Listening focuses on listening to wake up calls, doing interviews and triangulating to do your best to understand them properly, and to follow whatever recommendations are appropriate. If you do so you may find that the concept of karma becomes irrelevant. In addition, Integral Deep Listening does not view incarnation as an intrinsically painful place, pain as intrinsically bad, or avoiding pain as intrinsically good. There is nothing to escape from; to even try is to avoid yourself instead of practicing deep listening. There is nothing to escape to; to even try is to take yourself out of the here and now, which is the only place that life can exist.

Yoga as Meditation; Meditation as Yoga

Buddhism agrees with Hinduism that in order to become enlightened you need a spiritual discipline or yoga. However, Gautama subscribed to a much more narrow definition of yoga than was understood in India: “To enjoy good health, to bring true happiness to one’s family, to bring peace to all, one must first discipline and control one’s own mind. If a man can control his mind he can find the way to enlightenment, and all wisdom and virtue will naturally come to him.”

Gautama was clearly familiar with Hindu meditational yoga and accepted its fundamental doctrines. He expanded and elaborated on that system of meditation, adding as many as forty subjects of meditation, thirteen vows of physical restraint, and many aids for concentration. In a very early text, the Mahsatipahnasutta, Gautama teaches four subjects of meditation, the human body, sensations, thoughts and mind-objects. These are described as the “Foundations of Mindfulness.” What is interesting about this is that it implies that early Buddhist meditation focused on mental concentration on different subjects rather than consciousness itself. This difference is not trivial. It implies that some early stages of meditation were for early Buddhists what we now would call “contemplation” rather than meditation, that is, thinking about the human body, its condition and fate, thinking about physical pain and visual, auditory, gustatory, or sensate impressions, thinking about the thoughts that cross your awareness, or thinking about mental images. That this is “thinking about” rather than observing is implied by the inclusion of thoughts and thinking in the list. If this is so, early Buddhist meditation follows in the Hindu tradition of jnana yoga, which also relied upon contemplation of the human condition and truths about life.

In the Mahsatipahnasutta you are told to find a quiet place, free from disturbances, such as a forest, the foot of a tree or an empty house. Sit cross-legged with your body erect. Begin breathing mindfully by breathing in and out consciously and with awareness. When your mind is calm and brought to a point, take up the subjects of meditation. It includes the eight-fold method of Yoga advocated by the Yoga Sutras. These are sla, or moral purity, or setting and following an intention to act in an ethical manner, undertaken to prepare the mind for meditation; observance of internal and external purification through abstaining from unclean acts and thoughts; sitting cross-legged with an erect body; “mindfulness in regard to breathing,” involving an awareness of whether breathing is rapid or slow; withdrawal of the senses; fixed attention or trance; contemplation; and concentration.

In the commentaries 40 meditation objects are listed, including the kasinas – this is for samatha or tranquillity meditation where a single object is used to develop concentration (samadhi) and ultimately the jhanas. The most popular object of concentration seems to be the breath, and a whole sutta is devoted to this practice, the Anapanasati Sutta. While in the Yoga Sutras samadhi is the ultimate goal, in Buddhism it is only an intermediate step. Insight, or the realization of the true nature of life as embodied in the Four Noble Truths, is the ultimate goal. In Hinduism, while samadhi is the ultimate goal, it produces a number of other attainments, such as suspended animation, levitation, knowledge of past births and others’ minds as well as the mastery over the first cause which results in absolute independence. Both Hinduism and Buddhism assume the attainment of psychic powers is not only possible and desirable but also conducive to spiritual perfection.

Integral Deep Listening finds that there is little to no correlation between spiritual “gifts,” psychic abilities, or trance state access and spiritual development. Associating such state accomplishments with enlightenment implies that those who claim such accomplishments are enlightened, a conclusion that does not follow, since states are not developmental stages. State attainment may and usually does indicate proficiency in one line of development; it is a logical error to assume that because Einstein is a genius at physics that he will also have something valuable to say about meditation, opera, or construction materials. Just because a person can lucid dream or stay awake in deep sleep, it does not follow that they are enlightened. IDL also notes that there is no evidence, despite many people meditating in the 20th and 21st centuries, of suspended animation, levitation, precognition, and other psychic abilities as a consequence of meditation. Consequently, while meditation has been shown to be enormously effective at improving physical and mental health as well as improving problem solving, reducing stress, and improving both relationships and quality of life, it does not produce the psychic states or the transcendence of identity normally claimed for it. Why not? Interviewed emerging potentials rarely place any value on psychic abilities whatsoever. Why not?

While the implication is that such abilities are signs of being awake or enlightened, interviewed emerging potentials emphasize accessing broader and more inclusive perspectives on the world and translating those into actions that are in alignment with priorities of your inner compass. However, if you have a strong desire to develop such an ability, you can and will get feedback on your desire if you do IDL interviewing, as well as recommendations as to how best to proceed. Many interviewed emerging potentials recommend meditation; Integral Deep Listening highly recommends it as an essential element in your integral life practice.

IDL sees the benefits of meditation as balancing and integrating development on whatever level you are on, in addition to advancing the self line to higher levels. However, there is apparently nothing about meditation that will inherently advance the lines of cognition, empathy, ethics, or relationships. This is because we can point to famous mystics who were champion meditators who were clearly deficient in one or more of these lines. Therefore, the limitations intrinsic to your development on each of these lines, and particularly your worldview, since cognition is the leading line, are going to act as a natural anchor that results in your fixation at your current level of development. The implication is that you need a broad developmental approach that addresses all these different life areas, not just meditation. This is why IDL recommends an integral life practice.

Theravadin Meditation

Meditation is the practical core of Buddhism and its central yoga. To the extent that it is viewed as aimed at liberation from delusion and illusion it can be considered a dream yoga. While it can be practiced while dreaming and in deep sleep, Theravadin Buddhists have traditionally focused on waking up out of the waking dream. While they did not develop meditative practices associated with dreaming, lucid dreaming, or deep sleep, the extension of meditation into these states would have been recommended if such questions arose.

Theravadin meditation recognizes two varieties, samatha, or “tranquility,” and vipassana, or “insight.” In many Buddhist traditions, Samatha is done as a precursor to Vipassna. Samatha is “mindfulness of breathing” and is used primarily for calming the mind. Here are some traditional instructions: “Bring your attention to the small triangular area between your upper lip and your nostrils. Observe your inhalations and your exhalations. Whenever your mind wanders bring it back to an awareness of your breath flowing in and out.”

Vipassana is also watching your breath with awareness. However, it can also include contemplation, introspection and observation of bodily sensations, analytic meditation and observations on life experiences like death and decomposition. The main objective is to develop insight regarding the true nature of reality, which involve the “Three Marks of Existence,” impermanence, suffering, and the realization of non-self. These insights create freedom from samsara, nirvana.

Current “Mindfulness” meditation is descended from a Burmese Buddhist vipassana tradition developed in the 1950’s. It includes four stages of insight or jnana. In the first stage the meditator explores his body and then his mind, discovering the three characteristics of impermanence, suffering, and non-self. The first jnana consists in seeing these points and in the presence of attention, vitakka, and sustained discernment, vicara. Phenomena reveal themselves as appearing and ceasing. In the second jnana, the practice seems effortless. Vitaka and vicara both disappear. In the third jnana, joy disappears and only happiness and concentration are experienced. The fourth jnana is characterised by purity of mindfulness due to equanimity and leads to direct knowledge. The practice shows every phenomenon as unstable, transient, disenchanting, and the dissolution of all phenomena is clearly visible. The insight into the impermanence of all phenomena leads to a permanent liberation.

From this description you can see that vipassana, as traditionally taught as a process of insight and assumes a familiarity with and acceptance of basic principles of Buddhism. It is therefore different from its Westernized adaptations, such as Jon Kabat-Zinn’s widespread program for teaching mindfulness meditation. The popular Western adaptations are therefore probably more accurately called samatha than vipassana.

Because meditation is central to Theravadin Buddhism, the typical monk meditates three to four hours a day broken up into four or five different time periods. The rest of the day is filled with prayers, teachings, chores, and meals. Monks do not eat after noon. Consequently, meditation represents a major lifestyle choice and commitment for monks, and life in a monastery involves a degree of cultural, social, and ideological immersion that is difficult to compare to any other lifestyle. IDL encourages its students to explore many different approaches to meditation in addition to the techniques that it teaches. Long, committed practice to an effective approach to meditation is probably the one most important thing that anyone can do to bring balance and transformation into their lives. IDL believes that when effective, regular, and long meditation is combined with IDL interviewing and the application of recommendations that a synergistic effect creates growth at a faster pace than either practice by itself.

Theory of Dreaming

Theravadin Buddhism shares Integral Deep Listening’s focus on waking up from the dream of life. Consequently, it focuses its attention on waking yogas and has no historical interest in lucid dreaming. Another reason for its emphasis on waking experience is its comparative disinterest, in relation to shamanism, Hinduism, and Tantric Buddhism, in psychism, paranormal states, or adventures in heavens or hells.

Dreaming is important to Theravadin Buddhism, but it has nothing to offer that is different from traditional dream interpretation anywhere else in the world. Following Hinduism, Buddhism divides dreams and dreaming into categories of the spiritual and meaningful and the secular, profane, and meaningless. The latter are to be ignored and disregarded. Spiritual dreams may be from Gods or demons and are determined to be spiritual by their content, as perceived by the dreamer or dream interpreter. They are to be treated as literal revelations or metaphorical statements about great truths, as the personification of Buddha as a white elephant. Buddha’s mission was foretold in a famous dream by his mother, Queen Maya. The Buddhist scriptures mention five dreams related to Gautama, all of which are “spiritual,” in that they are precognitive or demonstrations of higher spiritual abilities.

Integral Deep Listening does not differentiate between spiritual and secular dreams because an interviewed pillow may prove to be as revelatory as the Buddha in a dream. You don’t know until you do an interview. Then you are free to arrive at your own conclusions. Was the interview about a “spiritual” or a “mundane” dream? What you will probably find is that after the interview the dream defies categorization, thereby throwing the entire system of categorization into question.

Life doesn’t differentiate between your waking and sleeping states, although because of the differing conditions of your mental filters it expresses itself differently in waking, dreaming, and deep sleep natural trance states. We have seen that in IDL all dreams are treated as wake up calls, to be listened to in a deep and integral way. This applies to your waking dream as well. The distinctions between spiritual and secular dreams are projections onto dreams by waking identity; waking interpretations by humans without the input of interviewed dream characters is embarrassing in their shallowness and ignorance to those who have experienced what is possible. Integral Deep Listening does not view waking identity and its preferences as the center of the universe. Instead, it views life as the center of the universe, and life is multi-perspectival, equally present in every occasion.

Other Characteristics Unique to Buddhism

Middle Way

The Middle Way, or Middle Path, the name Gautama gave his teaching, indicates a path of moderation away from the extremes of self-mortification and self-indulgence. It defines nirvana as a consciousness in which it becomes clear that all dualisms are delusions. Metaphysically, it indicates a desire to affirm a middle ground between disputes regarding whether things ultimately do or not exist, there is or is not God, or whether there is or is not a soul.

Integral Deep Listening views triangulation as a “middle way” between not two, but three extremes. The first has two aspects, depending on external sources of authority, such as experts, scripture, religious leaders, family, peers, psychics, professional codes, and work expectations; or depending on external sources of authority that have been internalized and made your own, so that you think they are “you” and “true,” such as internal parent voices, scripting, conscience, intuition, “God’s will,” revelation, visions, and dreams, as you understand them. The second extreme is soley to depend on your own common sense or judgment. The third extreme is to soley depend on interviewed emerging potentials. Each of these is, by itself, “extreme,” because it excludes two other important sources of objectivity for good decision-making. Each of these is, when conjoined with one other, ineffective, because it excludes another essential source of objectivity for good decision-making.

A middle way between these extremes involves consulting all three sources, and to do so effectively. For example, consulting phony, manipulative, or biased external sources is not going to yield effective decision-making. While consulting wise sources of external authority and guidance can be life-changing and absolutely essential, it is not the same as consulting your inner compass, nor is it expected to be. The two are not in competition. It also is not meant to replace using your common sense. The same is true for consulting conscience, intuition, internal parent voices, and most other internal sources of guidance, because these lack objectivity. They generally either validate what you want to hear and the choice you want to make (such as to believe the object of your infatuation really is your soul mate), or will tell you what you fear. If your common sense is not rational, that is, it is filled with emotional, logical, and perceptual distortions, then it will be disastrous to depend on it, with or without the other two. If you only trust and follow the recommendations of interviewed emerging potentials you are neglecting important feedback and help from the perspectives represented by others and your common sense. This is as much a mistake as erring to the other extremes.

Decision-making is central to spirituality because it is central to growth, to success and to failure. It involves all four quadrants of the human holon. Seeking external advice means consulting the external collective quadrant; seeking internal advice is to consult your internal collective quadrant; evaluating these with your common sense means to use your internal individual quadrant; acting on what you decide is to use your external individual quadrant. When you use all four quadrants in your decision-making you are more likely to make better decisions and thereby further your spiritual development. Relying on all three provides a system of checks and balances, with your common sense acting as the Executive branch of your internal government, external sources of objectivity as the Judiciary, and your community of interviewed emerging potentials as something like the Legislative. When all three are functioning, you are more likely to stay in balance and find a “middle way” forward for your life, avoiding extremes.

Dukkha (Suffering)

By choosing suffering as his starting point, Buddha wasn’t trying to be negative or pessimistic. He was instead pointing out a reality that most people spend their lives trying to avoid: that when you base your life on things that are impermanent the inevitable consequence is suffering. Suffering can be caused by loss, sickness, pain, failure, or the impermanence of pleasure and can be experienced as anxiety, dissatisfaction, unease, or distress. It may be experienced as illness, growing old, and dying; as the anxiety that comes from trying to hold on to things that are constantly changing; and as a subtle dissatisfaction pervading all forms of life that are impermanent and constantly changing.

Integral Deep Listening approaches suffering differently. It defines it as identification with the Drama Triangle in the three realms of relationships, cognition, and dreaming. To be in the role of persecutor, victim, or rescuer is to suffer. This is because to be in one role is to be in all three; to be in the Drama Triangle is to confuse your perception of life with life itself, because life does not do drama. Integral Deep Listening also differentiates between the suffering of victimization, as when you are in a car accident, and the suffering of being in the victim role of the Drama Triangle. It is enough to suffer as the victim of a car accident; it is another matter entirely to compound your suffering by feeling hopeless, helpless, powerless, and persecuted. Without the Drama Triangle you mostly have the suffering of physical pain to deal with; that is bad enough, but by itself much more easily dealt with than when you pile depression and anger on top of it, as occurs when people put themselves in the role of victim.

A third distinction that Integral Deep Listening makes regarding suffering is its perceptual subjectivity. At any point you can shift your identity into this or that perspective that is not suffering. This demonstrates that there is nothing intrinsic about suffering or anything inevitable about its presence in life. As the saying goes, “Misery is optional.” This why suffering is not ontologically grounded; there is nothing intrinsic to identity that says one must ever suffer. Such awarenesses allow a person to grow without being intimidated by suffering or to avoid choosing a path out of a desire to avoid suffering. A final awareness Integral Deep Listening has about suffering is that it is best viewed as a wake up call. Wake up calls are not to be avoided; they are to be listened to. This reframes suffering as an opportunity and aid to greater awakening.

The second truth in Buddhism, following that all things involve suffering, is that the origin of dukkha can be known. Within the context of the four noble truths, the origin of dukkha is commonly explained as craving (tanha) conditioned by ignorance (avijja). On a deeper level, the root cause of dukkha is identified as ignorance of the true nature of things. The cause of suffering is the desire to have and control things. It can take many forms: craving of sensual pleasures; the desire for fame; the desire to avoid unpleasant sensations, like fear, anger or jealousy.

Craving, the source of suffering for Buddhism, can be viewed as a desire for rescuing within the Drama Triangle. Ignorance generates feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and powerlessness associated with the victim role within the Drama Triangle. Wisdom then becomes the rescuer, which removes the persecution of craving. However, solutions to suffering do not lie within the Drama Triangle. If you escape craving by attaining wisdom, your rescuer becomes your persecutor. Why? Because wisdom is only one of six core values. To give it preeminence as the solution to suffering creates intrinsic imbalances, because it subordinates confidence, compassion, acceptance, inner peace, and witnessing. To avoid this problem, as well as this formulation of the Drama Triangle, you learn not to experience yourself as persecuted by your addictions because you come to understand that if you do, you put yourself in the role of victim, necessitating rescuing. Instead, IDL uses other core qualities, such as witnessing, to objectify craving so that you do not personalize it; acceptance to move you beyond preferring the end of craving; inner peace to choose freedom whether or not craving exists; confidence to seek balance outside the Drama Triangle whether or not craving and ignorance exist, and compassion to be kind to yourself and those others who are lost in craving and ignorance. All of these strategies are modeled by interviewed emerging potentials in ways that are tailor-made for our own particular “brand” of suffering.

Integral Deep Listening uses the six core qualities as antidotes to dukkha:

According to Buddhism there are three sources of suffering,

They are ignorance or delusion,

Attachment or craving,

and pride or self.

The remedies of these are found in the six core qualities.

Wisdom and witnessing are the antidotes to ignorance and delusion;

Develop them and you wake up and become enlightened.

Acceptance and confidence are the antidotes to attachment and craving;

Develop them and you become free and powerful.

Compassion and inner peace are the antidotes to pride and self;

Develop them and you become all things and sacred.

Anicca (Impermanence)

“In the sky, there is no distinction of east and west; people create distinctions out of their own minds and then believe them to be true.”

Buddha understood that when you create distinctions you create realities that are illusory. For example, “you” and “me” are linguistic and sensory-based distinctions that life itself does not make. The fact that we cannot conceive of life without them does not mean that they are intrinsic to life; they aren’t. Distinctions create useful and necessary stabilities where none exist. We then rely on those stabilities, become dependent upon them for our self-definition, relationships, and work. Most of them are not only harmless, they are helpful and necessary. However, believing in their reality and basing our sense of self on them is a common and honest perceptual error that invariably leads to suffering. At that point we are out of the flow of life. It is as if we were attempt to cling to water in a mountain stream.

Buddhism notes that all things and experiences are inconstant, unsteady, and impermanent. Everything you can experience through your senses is made up of parts, and the existence of things is dependent on external conditions. Everything is in constant flux, and so both conditions and things themselves are constantly changing. They are constantly coming into being, and ceasing to be. Since nothing lasts, there is no inherent or fixed nature to any object or experience. According to this Buddhist doctrine of impermanence, life embodies this flux in the aging process, the cycle of rebirth and in any experience of loss. Because things are impermanent, attachment to them leads to suffering.

For IDL, this is another way of talking about victimization by craving. When you are attached to something or someone, your craving persecutes you. You become its victim. You require rescuing, either by things staying the same or by changing; in either case they must conform to your preferences and expectations for you to be happy. Your preferences and expectations are relatively permanent; they do not shift to match reality. Consequently, your become attached to them. They become your persecutor and you their victim. You rescue yourself by associating yourself with those beliefs, activities, and people that validate your preferences and expectations.

Integral Deep Listening attempts to deal with this human predicament by encouraging identification with emerging potentials that are not attached to your preferences and expectations. They have their own that they may be attached to! There is no claim that they are free of craving or of suffering, only that they can help you leverage yourself free of those cravings to which you are attached. Different emerging potentials will be required, depending on the particular cravings, preferences, and expectations that are at work in your life at present.

Anatta (No Self)

“In separateness lies the world’s great misery, in compassion lies the world’s true strength”

For Buddhism, there ultimately is no such thing as a self that is independent from the rest of the universe. Gautama was brilliant to recognize this fundamental truth about life, that there is no such thing as any “thing” outside the perception of the beholder. This is because it is impossible to identify an independent, inherently existing self. The self only exists in dependence upon causes and conditions.

Here is the argument Theravadin Buddhism makes to support this conclusion. “If you look for the self within the body, you will not find it there, since the body itself is dependent upon its parts. If you look for the self within the mind, you cannot find it there, since the mind can only be said to exist in relation to external objects. Therefore the mind is also dependent upon causes and conditions outside of itself. Since the self cannot be said to exist within the body or mind, it is said to be “empty of inherent existence.”

Integral Deep Listening takes this argument for interdependence and relates it to the four quadrants of the human holon. If you look for the self within the external individual quadrant of the body and its actions, as biochemical reductionists do, you will not find it there, since bodies do not exist independently of environmental forces like gravity and atmospheric pressure, interior collective patterns of habit or instinct, and consciousness itself. If you look for the self within the mind, you cannot find it there, since consciousness is only found in the presence of material forms that embody it,[5] as well as social and cultural systems that contextualize it. If you look for the self within group identity, as the religious and nationalists do, you cannot find it there, because the self can only exist in terms of individual values, perspectives, consciousness, and action. If you look for the self within core values, as Socrates, Plato, and montheists do, you will not find it, because values do not exist apart from a manifesting form, relationships, and individual consciousness.

The importance of the doctrine of “neither self nor no self” is that it uproots both the source of fear and craving. The only reason you feel fear is because you think you are somebody that can die and that therefore needs protecting, or you fear you possess something that you can lose and that therefore requires protection. The only reason you feel cravings is because you identify with a sense of self that is “needy.” Because you have a body and live in a society of others who can steal, the need for protection is real. Victimization is real. However, when you become an emerging potential that does not have fears or cravings you make decisions without drama. While your cravings will return, because you cannot and will not hold on to that transformational emerging identity, that they depart when your attachment to a sense of self vanishes, demonstrates the principle. It is your attachment to your sense of self that creates suffering.

The Buddha saw that the solution is not to deny that there is a self, because it is an experiential fact. Instead, he denied the independent, autonomous existence of any self. This is very similar to how Integral Deep Listening views the personification of any perspective, whether that of a whale, a lightbulb, or yourself. It is not that these perspectives are not real, or are not associated with some “thing” that personifies them, but that their reality is dependent on the conditions that generate them. Eliminate those conditions and the “thing” is no more. A dream whale, light bulb, angel, or monster does not have an eternal soul; neither do you. It is your attachment to your sense of self that generates the delusion that such a permanent self exists. To the extent that attachments persecute you, you take on the victim role in the Drama Triangle. You now need an infinite variety of substitute gratifications to assuage your existential anxiety that maybe you will not only die some day, but that you really are nobody.

Integral Deep Listening views the concepts “I,” “my,” and “mine,” along with “you,” “yours,” and “ours,” as linguistic artifacts, arising with language and inseparable from it. Gautama rejected both the assertion “I have a Self” and “I have no Self” as ontological views that bind one to suffering. When asked if the self was identical with the body, the Buddha refused to answer. The experience of separateness arises from sensory embodiment and is reinforced in dream experience. This is rather like the Ptolemaic worldview. Because our eyes see the sun rise and set, the Earth must be the center of the universe. Because we experience our self as real, interacting with other selves, we must be real, separate, and permanent. Breaking free of this mythology is somewhat equivalent to Galileo attempting to demonstrate new truths to the Church Fathers; your daily experience will bring great pressures to bear to cause you to recant your foolishness.

All of the above amount to intellectual or rational observations that will not sway experiential and emotional realities. Consequently, IDL generally does not rely on such arguments. Instead it says, “Do the experiments yourself and draw your own conclusions.” The experiments are, of course, interviews of your choice of both dream characters and the personifications of life issues that are meaningful to you. Decide for yourself whether the perspectives you encounter have a “self” or not and how their sense of self-identity compares to your own.

Interdependent Co-origination

“Everything is interdependent.”

“All things appear and disappear because of the concurrence of causes and conditions. Nothing ever exists entirely alone; everything is in relation to everything else.”

Of the many brilliant contributions of Gautama, the concept of pratītyasamutpāda, interdependent co-origination, or that everything is interdependent, is perhaps the most brilliant. It is unique in the history of philosophy_ and the cornerstone of Buddhism, upon which the entire intellectual structure rests and depends. It is the basis for other key concepts, such as karma and rebirth, the arising of dukkha, and the possibility of liberation through realizing no-self, anatman. The way it is expressed in the original texts is as, ‘this existing, that exists; this arising, that arises; this not existing, that does not exist; this ceasing, that ceases’[6] In other words, a single cause does not give rise to either a single result or several results; nor do several causes give rise to just one result; but rather several causes give rise to several results.

The reason that interdependent co-origination is important does not rest on the truth or untruth of Gautama’s analysis of the factors leading to rebirth. It lies in its elimination of dualisms of all kinds, such as those between man and God, good and evil, right and wrong, heaven and hell, salvation and sinner, cause and effect. These implications were not clearly seen, nor were they spelled out for some six hundred years, until the brilliant mystic and philosopher Mahayana philosopher Nagarjuna did so in the Pratityasumutpada, “Constituents of Dependent Arising.”

This understanding undercuts the reality of shamanistic and shamanistically-derived world views by demonstrating that dualistic perception is not only a perceptual delusion but also a failure of the rational mind. This was not only important for refuting dualistic worldviews, but for creating a way for the thinking mind to first move beyond prepersonal and pre-rational belief systems, and then to objectify or transcend its dependence on itself. These are in turn requirements for a stable trans-personal and trans-rational worldview, which in turn is a prerequisite for maintaining stable, ongoing transpersonal anything. These are some of the reasons why it is highly unlikely that any true classical mysticism is much more than state access on the self-line. The requirements for more, such as advance on the cognitive line to vision-logic, much less beyond, just did not exist.

The fact that most religious and “spiritual” worldviews are either dualistic or are experientially monistic but are rationally still attached to the reality of substances, such as Atman and Brahman, in the case of Shankara, indicates that Buddha’s understanding of the conditioned, non-dual nature of life, still remain far ahead of their time. In addition, Buddhism itself has not absorbed or adapted to address these consequences: the side-tracking of belief in karma, samsara, the three realms, and the Two Truths Doctrine.

For Integral Deep Listening the importance of interdependent co-origination relates to the awarenesses gained by becoming this or that emerging potential. When you become a corkscrew, for instance, it speaks not only as an aspect of yourself, dependent upon your identity, perspective, experience, and memory stores, but adds to that its own unique and relatively autonomous perspective. Note the use of “relatively.” What the corkscrew says is dependent upon you and your identity and reality, and arises interdependently with your consciousness, yet offers a perspective that you agree with to a greater or lesser degree. You may not agree with it at all. How is that possible if it arises from within you? If it is a part of you then won’t you not only understand it, but agree with it as well?

When you become the corkscrew, it is your identity at that moment. Like Chuang-Tzu, the butterfly has created the dreamer. At that moment, your waking identity is interdependently co-originating with the imaginary corkscrew, which is who you are. You are imaginary; you are neither spiritual nor secular; you are in the middle between being and non-being. Once this understanding is experienced, through multiple interviews, the truth of interdependent co-origination is grasped, not as a logical, rational conclusion, but as a known and felt truth. So what? The result is that it becomes obvious that your sense of self is interdependently co-originated, a completely arbitrary construct that is dependent upon the locus of your perspective at the moment. It is only because that locus is normally stable and predictable, spread out among the habitual roles that you take in the round of your life, that a stable sense of self emerges and is maintained. Once you start spreading it among totally arbitrary and imaginary objects, yet discovering that they demonstrate characteristics that you normally retain to yourself in order to maintain the specialness and uniqueness of your sense of who you are, the illusory nature of an independent, non co-created existence is clearly observed.

This understanding will not turn you into a Buddhist, but it indicates that Gautama was onto something powerful and fundamental You do not have to accept the path of Buddhism to recognize and appreciate the clarity and helpfulness of some of Gautama’s basic ideas about life and how to live it.

Skandhas Generate Reality

“All form is comparable to foam; all feelings to bubbles; all sensations are mirage-like; dispositions are like the plantain trunk; consciousness is but an illusion: so did the Buddha illustrate [the nature of the aggregates].”_

“Skandhas,” or “aggregates,” are both another application of interdependent co-origination and an explanation of the specific mechanism by which it undermines both the concept and experience of an independent self or Self. By analyzing the constantly changing physical and mental constituents, the skandhas of a person or object, you are likely to come to the conclusion that neither the respective parts nor the person as a whole comprise a self. The five skandhas are:

Matter, or body, rupa,

sensations and feelings vedana,

perceptions of sense objects, sanna, (recognition, perception, conceptualization, cognition, reason)

mental formations samskaras, (habits, prejudices, predispositions, volition, intention, faith, conscientiousness, pride, desire, vindictiveness – various mental states), and

consciousness, vijnana.

The self, or soul, cannot be identified with any of its five constituents, nor is it the sum of these five parts. It is considered to be an illusory effect of the interaction of these five factors. The Buddha puts it like this, “A ‘chariot’ exists on the basis of the aggregation of parts; even so the concept of ‘being’ exists when the five aggregates are available.”

Integral Deep Listening encourages an understanding of these five elements, but defines them differently, as five different objects of perception: sensory experience, emotions, images, thoughts, and states, including perception itself. As you can see, there is a rough similarity to the Buddhist concept of skandhas, but Integral Deep Listening does not claim equivalency. It alters the order slightly, to reflect what developmental psychology says is the order of the differentiation of consciousness in humans. We first objectify our bodies with images, in which we are image-making beings observing our sensory reality. You can observe this in cats and six-month olds. We then objectify our images with emotions, becoming emotional beings observing both our images and sensory experience. You can observe this in dogs, two year olds, and while dreaming. We then objectify our feelings with thoughts, becoming rational beings observing our feelings, images, and sensory experience. You can observe this beginning with the acquisition of language and coming to fruition in adolescence. We then objectify our thought process through identification with a variety of different perceptual states, whether they are near death experiences, meditation, drug-induced highs, channeling, or becoming interviewed emerging potentials with Integral Deep Listening.

We know that these are states because they create disidentification with the state of waking identity and replace it with something else. The state objectifies waking cognition, emotion, imagery, and sensory experience. Of course, what you replace waking experience with determines to a large extent what you will get. If you replace it with deep sleep, you will mostly get unconsciousness. If you replace it with dreaming, you will mostly get emotionally-meditated experiences interpreted by your waking sense of self that is in the trance state called dreaming. If you replace it with near death experiences, drug-induced highs, or channeling, you still are interpreting those experiences through the filter of waking consciousness. Integral Deep Listening also does this, but not until an objectified perspective has a chance to speak. It then comments on the other four skandhas. Because you interview different emerging potentials, they provide objectivity toward each other, thereby objectifying the fifth skandha of states.

The Buddha taught contemplation of the skandhas as a type of mindfulness meditation, in which the monk saw each of the aggregates arising in consciousness and dissipating. The purpose of this exercise was to create a cognitive space between the skandha and attachment to it. It aimed to objectify the skandha: sensations, images, feelings, thoughts, or consciousness, and with them identification with a separate self.

Integral Deep Listening encourages its students to learn to identify these five types of identifications and objectify them when they meditate. This is discussed in the text, Transcending Your Monkey Mind: The Five Trees and Meditation.

The Three Jewels

Refuge in the Buddha

To take refuge in the Buddha has both objective and inner, esoteric meanings. The objective referent is of course the historical Buddha. The softening effect of time has produced the portrayal of an idealized human being, at least in the eyes of those Indian monks who recited the original scriptures for hundreds of years before they were written down. In this sense, the job of a Buddhist is to imitate the mind, heart, and consciousness of the enlightened Gautama.

The internal referent is to your own ideal and highest potential. Buddha’s mind in his earth body or nirmanakaya is frequently associated in Buddhist scripture with the greatest gem of all, the diamond, the hardest natural substance. In the Anguttara Nikaya Anguttara Nikaya,[7] Buddha talks about the diamond mind that can cut through all delusion.

This immediately raises a challenge. What happens when these two do not coincide? What happens when what you know, are told, and are taught about the path of the historical Buddha conflicts with your own ideal and highest potential? This question would be unlikely to ever arise among the great preponderance of historical or contemporary Buddhist practitioners, because the assumption is that they do coincide, and if they seem not to, it is only because of your ignorance. When you have right understanding you will see that the two coincide. Another way of asking this is to say, “Is each individual’s path always a universal one, when rightly understood?” If so, then it would seem that the external, objective Buddha is enough; one needs to ignore one’s own ideals and concept of highest potential, because the external is enough and the individual sense will only lead you away from the truth. Many people adopt this position. The opposite position is taken by others. The historical Buddha is merely an externalization of your own highest potential; he exists to direct you to listen within to your own path. If that is the case, then doesn’t it follow that at some point one can discard Buddhism and the historical Buddha in favor of one’s own wisdom?

Integral Deep Listening seeks a middle way between these two extremes. That is the purpose of triangulation. You are taught to consult with both external sources of authority, such as the historical Buddha, and your own emerging potentials, and then compare those answers with your own common sense. For IDL, the Buddha is a metaphor for one’s inner compass. Whether it is or not, or whether it personifies only some aspects of it while ignoring others, can be determined by conducting your own interview with the Buddha.

Refuge in the Dharma

Buddhism was a term coined by Westerners. The teaching itself is referred to by practitioners as “Buddha-dharma,” or simply as “Dharma.” In the earliest language of Buddhism, Pali, it is known as “dhamma.” This refers to the teachings recorded in sutta pitaka of the Pali canon that lay out the causes of suffering and the steps required to undo these causes. This is essentially a process of self-imposed disciplines involving various purifications, first of the body and relationships, and then of the mind, leading to insight into the internal causes of suffering and final liberation. Part of this path is helping others to do the same.

Theravadin Buddhism emphasizes personal discipline and the following of a previously laid out path rather than salvation through belief in a deified man. This is not the case in some forms of Mahayana, such as Amida Buddhism, but the original and majority Buddhist practice focuses on salvation through personal discipline involving aligning oneself with natural law, dharma, as understood and laid out by Gautama. Consequently, Buddhism tends to be based less on belief and faith than Chinese religion, the Western monotheisms, and many of the sects of Hinduism, and more focused on personal yoga – although it is not called that. This yoga is the Dharma.

There are a number of outstanding characteristics of Dharma that Integral Deep Listening also respects and encourages in its students. Neither Buddhism or Integral Deep Listening are approached as sectarian belief systems by supporters but as something open to empirical investigation. For Buddhists, this involves a causal analysis of natural phenomena. For Integral Deep Listening, it involves the investigation of any and all perspectives. Because both are based on empiricism they are open to scrutiny, testing, and falsifiability. Both welcome it. Those who follow the injunctions will see the results for themselves by means of their own experience. Both work in the here and now. All are invited to come experience the results for themselves by putting it to test in their own lives. Both require personal experience; hearing and reading about a yoga is not sufficient to understand or evaluate it, nor is it something that can be communicated by a teacher, although teachers are necessary to tell you where to look and to provide objective feedback. Each person is personally responsible for his or her own practice. While Theravadin Buddhism holds that the practice of the Dhamma is the only way to attain the final deliverance of Nirvana, Integral Deep Listening believes that there are many ways but that some are superior to others. In addition, instead of seeking an ultimate, unchanging state, Nirvana, Integral Deep Listening is a developmental tool that supports an ongoing process of awakening, regardless of one’s level of development. Its purpose is to access and maintain higher stages of development, wherever you are in your development, rather than to attain some ultimate state.

Refuge in the Sangha

“No one saves us but ourselves. No one can and no one may. We ourselves must walk the path.”

“Work out your own salvation. Do not depend on others.”

This is fascinating, in that it is contradictory. While insisting on an individual approach to enlightenment, Buddhism depended on communities of monks, not autonomous individual effort. It also relied on prelates as teachers, instructors, and gurus in right living and meditation. In these teachings Buddha and Buddhism claims to break from Hinduism in its reliance on a guru. However, in practice Buddhism depends on one’s own effort in the context of a teaching community where the officiating monks and the scriptures serve as gurus.

Sangha means “association,” “assembly,” “company” or “community.” It usually refers to the monastic community of ordained Buddhist monks or nuns. The ariya-sangha, or “noble Sangha” is a subgroup within this community of those who have attained a higher level of realization and who functionally serve as gurus within the monastery. The monastic life is considered by Buddhism to be the safest and most suitable environment for following the dharma due to the temptations, distractions, and demands of secular living. The sangha not only provides a refuge for practicing meditation; it preserves the teachings and traditions of Buddhism and provides spiritual support for the surrounding community. Buddhist monasteries are teaching centers for monks and the surrounding community alike.

Monks and nuns chant daily the following description of the Sangha: