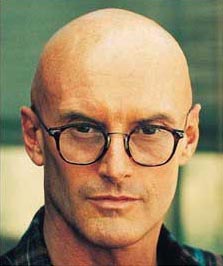

This is another important book by Ken Wilber, the most important integral philosopher and psychologist in the world today, but one that many people will put down somewhere in the first chapter, if they make it through the introduction. That’s because the first chapter is probably the most conceptually challenging thing he’s written to date. Although people can get thrown by words they are not familiar with or references to authors and sources that they know nothing about, most of Wilber’s writing over the years is conceptually simple. The challenge of the second chapter is different, as we shall see.

First, an overview. What exactly is Wilber attempting to accomplish with this book? Wilber is attempting to reconstruct the great truths of the wisdom traditions of the world’s religions but without their metaphysics. These “metaphysics” are assumptions about the nature of reality that have been thoroughly discredited by modernity (Kant) and post-modernity’s insight of the inherently contextual nature of all truth, which makes it relative. Basically, he sees spirituality as a necessary engine for human evolution, along with the arts, sciences, and ethics. But unlike arts, science, and ethics, spirituality was derailed by the Western Enlightenment in the 1600’s and 1700’s. Wilber has written this book to rehabilitate spirituality in the eyes of Western intellectuals and everyday people around the world who have lost faith in traditional religion but don’t know where to turn. It is true that most everyday people will not read this book, but the intellectuals who are at the top of their pyramids of influence will read it, and they will translate its concepts into forms that everyday people will grasp. So Wilber is writing for the opinion setters of the day, those who are influential, and those whose ideas are respected by broad numbers. His audience is, as always, those who not only have a college education but who are well read and broadly educated.

Wilber’s introduction is a succinct, compact introduction and overview of his AQAL (all quadrant, all levels, lines, states, and types) model. Everyone should read this chapter over until they “get it” or they will get lost in the rest of the text. While it is truly an introduction, it is also truly the first chapter of the book. Don’t skip over it! For those who have been following Wilber ‘s writing for years, this introduction is an excellent and lucid summary of his model, which is the broadest, most powerful explanatory model of everything that exists in the world today. Toward the end of the chapter Wilber discusses implications of the integral model for medicine, business, ecology, and other fields. Discussions about the relationships among fields of knowledge or discussions about the basic questions driving particular fields of knowledge will flounder on their own inherent contradictions unless they take place in the context of Wilber’s integral model. It’s that important.

Wilber’s Chapter One, “Integral Methodological Pluralism,” starts with a daunting name and gets more intimidating from there. Wilber is always revising and expanding his model. To that end, he has more deeply considered the implications of the four basic perspectives that are inherent in every holon and determined that each includes two perspectives, doubling the number of fundamental perspectives to be taken into account to eight. So if you thought four were a lot, try eight! However, Wilber makes a very good case for these eight, because he points to well-respected fields of knowledge that are representatives of each. But let’s back up and take a look at the four quadrants. Wilber contends that everything has an interior and an exterior aspect as well as an individual and a collective aspect. Simple, obvious, and brilliant. Can you think of ANYTHING that doesn’t have those four aspects?

Let’s take as an example something abstract, like the following sentence: “Wilber is pedantic and egotistical and his system is grandiose.” These written words are measurable, objective things that we can diagram. The sentence is a distinct, individual expression that can be objectively measured. These are qualities of the upper right quadrant, which involves individual exterior events and “facts.” In this regard, this sentence is called a “signifier,” because it is what concretely exchanges information between the two of us. There are also, however, shared meanings for these words. Meanings are interior, not exterior and, to the extent that they are shared, they are collective. So the meaning of this sentence is called the “signified,” and it is an interior collective or lower left aspect of the sentence, very different from the first aspect that we just mentioned. However, what exactly is being “signified?” Am I being serious or just facetious, playing devil’s advocate and poking fun at a common criticism of Wilber’s by showing how it also is a product of his model? To know for sure, you have to have access to the upper left, or interior individual aspect of this sentence, namely the referent thoughts and feelings that they represent. Unless I tell you, you can only guess, because upper left quadrant experiences, although real, are by nature private. The fourth aspect of this sentence has to do with what this sentence says about our exterior collective, or social relationships. We are members of groups of people who are interested in spirituality and the writing of Ken Wilber. So regardless of who we are or our particular perspectives, we all share in all four of these aspects of experience.

Each of these four perspectives can be experienced from the inside or investigated from the outside. Here is a summary of the eight perspectives, which Wilber believes have always existed but have only recently been differentiated or objectified. Wilber believes that all of these are forms of empiricism, in that they are ways of knowing that can be subjected to appropriate truth tests and verified.

#1: When we think, feel, sleep, dream, or meditate, we are having personal interior experiences of the upper left quadrant. When you study your own experience by say, observing your thoughts in meditation, you are practicing phenomenology. This is what mystics do and what you experience when and if you are enlightened. Without this perspective you wouldn’t think, feel, dream, or be able to have mystical experiences at all.

#2: When you study what is going on in people when they think, feel, sleep, dream, or meditate, you are attempting to evaluate personal interior experience, not directly experience it yourself. When you do such evaluations you are practicing structuralism. What you come up with are developmental models that depict the evolution of consciousness and your own personal development. Structuralism creates a road map to guide your own growth. Without it you are more likely to misunderstand your experience and waste a lot of time in confusion.

#3: When we communicate, as in the sentence, “Wilber is pedantic and egotistical and his system is grandiose,” we share a common or collective experience that is interior for each of us. I have my meaning and you have yours, but out of that a sense of shared meaning arises. You are interpreting what I am saying and I am thinking about how you are hearing me and what interpretations are being made by you. This study of interpretations is an unavoidable and important part of life that has been given the unsufferable name of hermeneutics. Just think of it as the meanings we make out of people, words, and things. These shared meanings are called culture. Without meanings, life is…meaningless!

#4: There are people who study the way people make sense of their social worlds. It considers the cultural and linguistic contexts in which ALL experience is embedded. This is called ethnomethodology. You use it when you try to understand how other people arrived at how they look at things. When you attempt to understand how Wilber arrived at his conclusions in Integral Spirituality, you are practicing ethnomethodology!

#5: The perspectives of the interior of the behavior of organisms is not the study of thoughts and feelings. It is the study of how brains of frogs and humans make sense of the world. This is called cognitive science or autopoiesis (self-creation). It is more the study of mechanisms of perception than of consciousness itself. Without it, it would be impossible for you to learn how and why you think the way you do or how you create the interior neurological realities that in turn create your perception.

#6: When individual behavior is explored from the outside we are doing traditional science. We make hypotheses in our minds and then test them out in the real world. For example, I could hypothesize that most people who read these words are sitting down. To test it I would either have to ask you or I would have to have you on camera or in some way observe you, say by sending my astral double over as a scientific voyeur. Also, if you hook me up to an EEG while I am meditating, you are doing traditional science. However, you can’t measure my state of consciousness but only its neurological correlates in the form of patterns of electrical neuronal discharges in my brain.

We can see that part of what Wilber is doing is breaking science’s stranglehold on knowledge by making a strong case for seven other forms of empiricism. Here are the remaining two:

#7: When you look at social groups from the inside, you are looking at the way their members communicate with each other. These patterns of group communication are how groups create themselves, in a process called social autopoiesis. Those of us who form an ad hoc group of those interested in discussing Wilber’s ideas and their applications are also practicing a type of empiricism that is internal to our social group. We develop our own shared criteria for determining what the rules for that communication are to be. Without it you will have no way of knowing how to communicate within any and all groups – your family, your network of friends, your place of work.

#8: When you look at social groups from the outside you are doing systems theory, chaos theory, and social psychology. This is how you understand your relationships with others and your relationship to the world.

So those are the eight perspectives that Wilber says are all basic, unavoidable, necessary, and equally important to human experience and, in fact, to understanding all holons. What do YOU think? If you had to ditch one, which would you get rid of? Now, imagine your life without it!

Wilber says that the recent realization that all these perspectives exist has created massive problems for traditional religions and for the credibility of people who have claimed to be enlightened in the past. Because neither religions nor enlightened sages took into account most of these perspectives, just how spiritual, just how developed, just how enlightened could they really be? This is the main reason why religion and spirituality have both lost credibility in the modern world and among intellectuals, according to Wilber. Because religion and spirituality do not take most of these perspectives into account they choose to remain both naïve and ignorant. Their credibility is undermined. So, what is to be done about it?

Wilber believes that it is only spirituality that can heal the discounting of interior experience that is found in science and that only spirituality can overcome the yawning gap between rational scientists and egalitarian liberals, on the one hand, and religious true believers on the other. So most of the book is about laying out a description of that spirituality.

In Chapter Two, Stages of Consciousness, Wilber makes the following points:

• When we reduce transpersonal experience (like a near-death experience) to prepersonal experience (psychotic hallucinations), as science does, we are guilty of the reductionistic version of the pre-trans fallacy. Most scientists, from Freud to Skinner to Watson and Crick, commit this fallacy.

• When we elevate prepersonal experience (like voodoo trance) to transpersonal experience (thinking it is a mystical experience), as Carl Jung and New Age thought do, we are guilty of the elevationistic version of the pre-trans fallacy.

• The developmental progression disclosed by structuralism gives you ways of interpreting your experience that you just don’t get when you are subjectively immersed in it, as you do when you are say, meditating.

• Wilber uses the concept of an “integral psychograph” to talk about different developmental lines, such as cognitive, kinesthetic, emotional, moral, aesthetic, and spiritual. The idea is that we need balance in development, which means that we need to pay attention to important core lines that we are behind in.

• Wilber explains the interaction between stages of development that occur on every line, and the different developmental lines themselves. On pictures after page 68 and also on pp. 248-9 he summarizes the stages as viewed from different structural models.

• Wilber has moved partially away from the use of colors derived from Spiral Dynamics to talk about stages and has returned to a modified version of the electromagnetic spectrum. This is a good thing, because the SD colors were arbitrarily chosen to reflect a higher personal pluralistic and egalitarian perspective which is to favor only one of some ten possible perspectives. I say Wilber settled on a “modified,” version of the electromagnetic spectrum because in my opinion, he had such an investment in using Spiral Dynamics colors to talk about certain levels (in particular pluralistic and egalitarian “green,”) that he has tinkered with the entire spectrum to make it fit his bias. So while I am still not happy with his version of the spectrum, at least it acknowledges that there is a genuine, “real” vibratory hierarchy that is far from arbitrary. That’s the main point.

In Chapter 3, States of Consciousness, discusses natural and trained states of consciousness.

• Think of these states as dealing with four different types of mystical oneness: nature, deity, formless, and non-dual. They represent a horizontal opening on any developmental level.

• These natural states (waking, sleeping, dreaming) do not show development. This means they can be experienced in their fullness by infants.

• Trained (i.e., through meditation) states (nature, deity, formless, and non-dual) do show development.

• Both the literature and scientific evidence demonstrate that meditation reveals very sophisticated stages of trained states of progressive enlightenment.

Chapter 4, States and Stages, differentiates stages of consciousness from states of consciousness. This is very important and a major contribution to man’s understanding of spirituality. Most writing about spirituality is dreadfully confused because it does not understand the distinctions made in this chapter. Here they are, in a nutshell:

• States are impermanent; stages are permanent. This means that having an experience of oneness with God when you are experiencing life from say, the rational level, is a) not going to last because it’s a state, or b) will not transcend and include higher stage experiences of oneness with God. It won’t, because you haven’t yet reached those higher stages yet; you’re still at rational.

• All states are available at every level. That means you can be at a prepersonal stage of development and have an experience of non-dual enlightenment.

• Wilber gives a lot of examples of awakenings at different levels of development.

• He believes that to make sense, “enlightenment” must take into account 1) whether the experience is passing (a “state”) or permanent (a “stage”), 2) the type of experience of oneness (“Is it nature, deity, formless, or non-dual?”), and 3) the average over-all stage of development of the individual. (This is an average of their major developmental lines.)

• Wilber also differentiates among four different ways of using the word “spirituality.” 1) the highest level of any developmental line, 2) a specific developmental line, 3) a spiritual or religious experience, and 4) a specific attitude. This too is a highly important insight, because it clarifies just how hopelessly confused all most all discussions about spirituality are. Why? Because people are either using different definitions of spirituality or are switching from one meaning to another as it suits them.

In Chapter 5, Boomeritis Buddhism, Wilber discusses what can go wrong with development in general and with spiritual development in particular. He uses the example of Western Buddhist meditators who have an individualistic, egalitarian, pluralistic (higher personal) perspective which they bring to their practice of meditation.

• Boomeritis is an example of the pre-post fallacy in that preconventional narcissism is mistaken for transpersonal world-centric awareness. “The harder you could feel your ego, emote your ego, and express your ego with real immediate feelings, the more spiritual you were thought to be.”

• High transpersonal experiences and meditation instructions were misinterpreted by people at high personal from a pluralistic, egalitarian perspective. Wilber thinks of this as being like a virus in a system, causing teachers of meditation to communicate these misperceptions to their students.

• People can’t spot this virus from within their own meditative practice. Understanding and using all eight perspectives creates objectivity that reduces the likelihood that one will fall prey to the virus. When they do, they will have more tools for figuring out how to get unstuck. So having “correct views” by being able to use all of these perspectives as needed is recommended.

• To this end, Wilber recommends that meditators supplement their phenomenological (individual interior) perspective with structuralist developmental models, many of which he discusses in the text. He recommends taking up an integral life practice, which he discusses toward the end of the text. Finally, he recommends orienting personal spiritual practice in an integral or AQAL framework.

In Chapter 6, The Shadow and the Disowned self, Wilber discusses how meditative traditions have traditionally ignored and repressed thoughts and feelings and what a major contribution the West has made in its understanding of the necessity of acknowledging both before transcending them. He goes on to outline an easy method of doing just that.

• He defines the “Shadow” as “dynamically dissociated 1st person impulses.” (“1st person is the person speaking, 2nd person is the person being spoken to; and 3rd person is the person or thing being spoken about.”) Wilber’s point is that unrecognized impulses get projected onto the external world. We see others doing to us what we are actually doing to ourselves. “I see my neighbor as a control freak when I am actually the control freak, but don’t recognize it…”

• Meditation lacks the objectivity to recognize or respond therapeutically to these disowned impulses. As a result, they simply get carried forward so that a person becomes enlightened, in that they are stabilized at a high state and perhaps at a high stage, yet unaware of their own shadow.

• Instead of letting go of everything, Wilber makes a case for first owning and accepting impulses fully and then letting them go.

• I’m not sure what it’s doing in this chapter, but Ken next talks about vertical enlightenment (transcending and including up through the developmental stages) and horizontal enlightenment (becoming one with all states – gross, subtle, causal, nondual). Later in the chapter he talks about how proper meditation can allow one to jump two vertical stages in four years. Nothing else can do that!

• Wilber then talks about the damage that repressed, unaddressed shadow does in meditators.

• Wilber describes the 3-2-1 process of reowning the self before transcending it.

In Chapter 7, Wilber makes a major contribution to systems theory by demonstrating how many theorists, from Capra to Chopra mistakenly see groups as living organisms as including individuals. Wilber points out that groups lack what Whitehead called a “dominant monad;” essentially, that means that individual group members don’t have to do what the group as a whole wants and that therefore individuals are not interior to groups.

• Instead of individuals being interior to groups, groups are the collective aspect of individuals. What is interior to groups is their communication. Systems theorists (mostly perspective #8) have missed these basic and critical distinctions.

• Wilber emphasizes the consciousness of “we” as a particularly effective doorway to spiritual development.

• Individual holons go through mandatory stages of development. Social holons don’t. The cycles of development social holons go through, such as societies, businesses, and civilizations are horizontal, in that any group at any level or stage can go through them. They are usually mistakenly described as vertical stages in most texts on the evolution of cultures, societies, and systems.

• Social holons change their stage of development as their membership varies. They can move forward or backward, while individual holons only move forward, at least in some lines, such as ethical.

• Social holons do not have four quadrants. They lack the internal individual “dominant monad.”

• Spirit in 2nd person is experienced as a devotional relationship based on love that deepens into compassion. Wilber emphasizes its importance.

• Wilber believes that most writers on spirituality have not grasped the “we” dimension of spirit. Partially this is because they have been trying to escape a suffocating personal depiction of God from their youth but mostly it’s because the exteriors of “we” are very difficult to see.

In Chapter 8, The World of the Terribly Obvious, Wilber discusses scientific empiricism (#6) and autopoiesis (#5). He discusses scientific reductionism and its attempts to reduce God to brain states.

• Higher order transpersonal experiences cannot be experienced or be said to exist for those who are not at those levels. Therefore they will be misperceived if seen at all by those observing them from personal levels of development, as scientists do.

• The basic problem of this perspective is that it does not grasp the relative nature of all individual experience, which is the basic insight of postmodernism, which gives priority to the intersubjective matrix of interpretations and cultural meanings in which all individual experiences are embedded.

Chapter 9, The Conveyor Belt, is the heart of the book. Everything to this point has been laying a complex, sophisticated theoretical foundation for this chapter.

• Because everyone must navigate every stage of development in turn from birth, the average stage of people alive on the planet today is high prepersonal egocentric-mythic to low personal ethnocentric. 70% of the people on the planet are controlled by the world’s great religions. That’s less than at any time before in the world’s history, but it’s still huge.

• There is a “vertical component crash” between individuals and cultures stuck at ethnocentric and below and the 30% that have evolved into rational and worldcentric perspectives.

• Terrorists are stuck at mythic and ethnocentric perspectives with a prepersonal narcissistic self-image, the kind you normally find in four year olds.

• The problem is that those stuck at these pre-rational belief systems cannot grow because the rational world view dismisses them as irrational and foolish. So they cannot grow without abandoning their prepersonal belief systems, which they will not and cannot do, because they are the belief systems of their entire culture.

• With the Enlightenment, Western intellectuals actively repressed any higher levels of their own spiritual intelligence. Reason was the answer. “Death of God” meant “Death of the Mythic God,” which is the one 70% of the world believes in today.

• Wilber describes this problem as a new type of fallacy, a “Level-line fallacy.”

• In disowning the Mythic stage of development rational intellectuals also disowned the entire spiritual line of development. They mistook mythic spirituality for ALL spirituality. This insight of Wilber’s is brilliant and right on. You are left wondering why no one has spotted it before. (Wilber says they missed it because it wasn’t there when the cognitive, aesthetic, and moral lines were differentiated at the onset of the Enlightenment. It had already been dismissed and dropped by serious thinkers.)

• Wilber says there are four different multiple intelligences: cognitive, aesthetic, spiritual, and moral. All were differentiated and advanced with the Enlightenment, except the spiritual intelligence/line/judgment, which was brutally repressed.

• With the repression of that line, there was no way for prepersonal mythic spirituality to evolve. Any movement beyond the rational was discredited as well, leaving everyone who made it to rational stuck there in their development. “Modern liberal intellectuals no longer had religion, they only had art and morals.”

• The “grand displacement” occurred: “Because the line of ultimate concern (spirituality) was repressed at amber (mythic), and because this is nevertheless a still active multiple intelligence, that inner judgment of ultimate concern was displaced from religion to science. In the modern world, it was now science that was implicitly felt to give answers to ultimate questions, and science to which ultimate faith and a pledge of allegiance should occur.”

• Absolute science is scientism, which collapses the four quadrants into the upper right. The spiritual line of development gets repressed along with the mythic stage of development.

• There are two parts to the problem: 1) repression of spirituality by rational intellectual culture and 2) fixation at the mythic stage for those who don’t have a way to express their spirituality in higher developmental stages. That means almost everybody living in religion-dominated cultures.

• Rational intellectual culture needs to stop hating mythic religion and start appreciating spirituality as it naturally expresses itself at the rational stage, including agnosticism and atheism. It also needs to understand that spirituality acts as a developmental conveyor belt for everyone, because everyone must move through the lower stages, and only the spiritual line provides fundamental meaning to life through addressing issues of ultimate concern. People need “real” myths at a stage of development, and only the spiritual line provides it.

• Wilber is calling for the de-repression of the developmental line of spiritual intelligence.

• He also calls for religions to make training in meditative states part of the core of their message and meditative training in stage appropriate ways made available at every stage of development. Such training will speed evolution through the stages.

In Chapter 10, Integral Life Practice, Wilber addresses what he thinks that state training should look like as part of an over all plan for life integration and development.

• Wilber’s model is very sophisticated, including at least six or seven practice choices in each of the following areas: the core of body, mind, spirit, and shadow, and the auxiliary areas of ethics, sex, work, emotions, and relationships.

• Each of these areas has one or more “gold star” or “highly recommended” practice: Body: F.I.T., ILP Diet, 3-body workout; Mind: Integral (AQAL) Framework; Spirit: Big Mind Meditation, Compassionate Exchange, Integral Inquiry, the 1-2-3 of God; Shadow: 3-2-1 Process; Ethics: Integral Ethics; Sex: Integral Sexual Yoga; Work: Work as a Mode of ILP; Emotions: Transmuting Emotions; Relationships: Integral Relationships, Integral Parenting.

• Wilber repeatedly points the reader to resources at the Integral Institute,

Wilber includes several appendices that are actually part of the text and need to be read. They amount to fully a quarter of the text, not counting the extensive footnotes that take up almost all of some pages of the text.

Appendix I, From the Great Chain of Being to Postmodernism in 3 Easy Steps, deals with the rehabilitation of mysticism by making it compatible with modernity and postmodernism.

• The first problem is that the Great Chain of Being views spirit as above and beyond mind and matter. The solution is to view spirit as interior tomatter, as the two left quadrants of the human holon. This addresses the basic criticism of modernity.

• The second problem is that the Great Chain of Being views spirituality as basically an individual and interior expansion. The solution is to view spiritual development as also collective and thereby including the bottom two quadrants of the human holon. This addresses the basic criticism of post-modernism.

• The third problem is what to do with the subtle levels of energy talked about in all the mystical and esoteric traditions: etheric, astral, psychic, causal. Wilber’s solution is to associate increasing complexity of form (in the upper right quadrant) with increasingly subtle levels of energy.

As if he hasn’t covered enough, in Appendix II, Integral Post-Metaphysics, Wilber tackles the issue of what a healthy spirituality looks like once it sheds the assumptions that cause it to be discounted and deemed irrelevant by modernity and post-modernity. Both religion and spirituality have been discounted since Kant showed that all of our concepts, including “God” and “spirit” are conditioned by natural cognitive structures. What we think is real and existing “out there” is only perceived and understood in terms of the way our minds organize the experience. Metaphysics doesn’t grasp this.

• Wilber launches into an extensive discussion of what it means to be enlightened in previous historical epochs and what enlightenment now would consist of. Very interesting reading, starting at the bottom of p. 237 and going all the way through p. 248. He concludes by stating that levels of reality do not pre-exist but are created by the evolution of consciousness. This means that enlightenment, while always equally free and empty, becomes more “full” as habits of consciousness create higher stages. Wilber believes his answer satisfies the criticisms of modernity and post-modernity without postulating a metaphysical foundation for spirituality.

• “Nobody ever has any truth, just various degrees of falsehood.”

• “Things” do not exist objectively in a pregiven world. “All real things are first and foremost perspectives.” You locate something in the universe by determining the level on which it exists and by determining the quadrant in which it exists. You also must take into account the level and perspective of the perceiver!

• A “quadrant” is a perceiving subject’s perspective; a “quadrivium” is the object’s location as it is perceived. This is because only individual holons have all four perspectives (artifacts like chairs lack a “dominant I,” but all objects can be looked at from any of the four quadrants.

• Wilber goes on to get very sophisticated about this, basically laying out his epistemology, or what can be known and how you can know it. He explains why and how any statement can be (and should be) located in terms of perspective and stage. He goes on to suggest letter and number designations as shorthand for identifying any statement according to where it exists and who can see it…Whooooboy…

• Wilber now makes a very critical and important point. After you have gone to all the trouble to specify the “Kosmic address” of God, Santa Claus, or imaginary numbers, you “must be able to specify the injunctions (instructions) necessary for the subject to be able to enact the Kosmic address of the object.” In other words, for you to just give an address but not provide the injunctions by which that address can be verified, you are just doing metaphysics. What Wilber is doing here is creating a very rigid epistemology not only for spirituality but for every truth claim of every kind. This could have been (and probably should be) a book all by itself. It’s huge.

• He sums the last point up in a succinct and revolutionary way: “Any language other than injunctive is metaphysics.” Wow! This is the most important part of the book, and it’s in the second appendix!!! “No injunction, no meaning, no reality. Just metaphysical gibberish in an age that is no longer capable of being impressed by such…”

In his FINAL appendix, number III, The Myth of the Given Lives On, Wilber gives a series of examples of areas of thought that are stuck in a metaphysical, pre-integral world view.

• Both the sciences and the humanities rejected introspection, interiority, spirituality, and subjectivity in the 20th century.

• Wilber gives a terrific summary of the rise of post-modernism and its attack on modernism in its phenomenological forms (existentialism, humanism, phenomenology).

• Wilber thinks that contemporary writers on spirituality like Capra and Chopra have done little to rehabilitate spirituality for intellectuals. They write for a popular audience that has not come to grips with the serious questions, much less the disheartening answers, that modernism and post-modernity pose for spirituality. Their mistake is that they have attempted to demonstrate that mysticism has modern scientific support in an attempt to give it the credibility necessary to have it be accepted by the humanities. “This was EXACTLY THE WRONG MOVE in every way. The enemy was never science, which won’t listen anyway. The enemy was the intersubjectivists. And by showing, or trying to show, that spirituality could be grounded in quantum physics, or dynamical systems theory, or chaos theory, or autopoiesis, they played right into the hands of the intersubjectivists.” (p. 282)

• Wilber’s point is that the post-modernists reject all forms of reality that do not take into account the relativism created by the consideration of unavoidable contexts created by language and interpretation. Science is as guilty of this as the humanities in their critique, which Wilber accepts.

Finally, Wilber critiques a number of contemporary and classic works on consciousness, mostly to point out where respected thinkers are missing the point. His critique of William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience is amazing and his critique of meditation in his piece on Daniel Goleman’s, The Varieties of Meditative Experience, is fairly astonishing, coming from a very practiced and advanced long-term meditator like Wilber: “Meditation is still hobbled by the myth of the given because it is still monological; it still assumes that what I see in meditation or contemplative prayer is actually real, instead of partially constructed via cultural backgrounds (syntactic and semantic).” “Meditation is the extension of the myth of the given into higher realities, thus ensuring that you never escape its deep illusions, even in Enlightenment…” “Again, meditation is not wrong but partial, and unless its partialness is addressed, it simply houses these implicit lies, assuring that liberation is never really full, and even satori conceals and perpetuates the myth of the given…” (pp. 289-90)

• On pages 291-2 Wilber writes a devastating critique of the “new physics,” including What the Bleep Do We Know? (on pp. 294-5).

• An equal opportunity paradigm basher, Wilber next takes to task a post-modernism that refuses to recognize stages of development beyond language and personal. Pp. 295-6.

Here are my thoughts about this text:

• Ken Wilber has once again proven himself to be the most brilliant, revolutionary, important thinker of our time. Anyone who, from this point forward, does not or will not take his model into consideration while attempting to advance knowledge on any subject is just not on the “A” team. They are announcing their contributions to be “pre-integral” in the big picture of human evolutionary thought. To repeat myself: Yes, it’s that important.

• If a person reads and re-reads this text until they understand it, they will get the equivalent of a Ph.D. in a branch of philosophy called epistemology, or “how we know what we know,” “what is true,” and “what is real.”

• I have already mentioned my problems with Wilber’s present color layout. I have my own preferred solution, but I won’t bore you with it.

• Wilber would have strengthened the text and tied in the difficult first chapters with the important last chapters if he had shown how each of the eight perspectives could be used to move people from mythic to worldcentric rational in the context of an integral life practice.

• It would also have been helpful if he had talked about how an integral life practice shows up at each stage. What’s different?

• Again and again Wilber tells his readers that they must take the arguments of post-modernism seriously. He is convinced that spiritual studies cannot and will not be rehabilitated in the West until this is done.

• Wilber would probably say that whatever thoughts and feelings are aroused in you as you read this text reflect your average level of development. What ideas don’t you like? Explore your reasons why. Are parts of yourself threatened by them? If so, what parts?

• Wilber has created a classic. I would not say that it is easy, but it is clear. It’s just that it includes an ENORMOUS amount of information, most of which will be new to most readers. About a fourth of it was new to me, and I’ve read everything Wilber’s written that has come to my attention, at least once, many twice. So if it seems somewhat overwhelming, that’s a good sign. It means you’re in the right chair, in the right class, in the right school. Keep learning.

Joseph Dillard

IntegralDeepListening.Com

DreamYoga.Com