What are world views?

Why are they so important?

What are the transformations in World View that led to the development of Integral Deep Listening?

The World View of Integral Deep Listening

“I believe that if we really want human brotherhood to spread and increase until it makes life safe and sane, we must also be certain that there is no one true faith or path by which it may spread.” – Adlai E. Stevenson

This wise quote indicates an awareness of the need for multiple world views, or what is called “multi-perspectivalism,” a fundamental characteristic of an integral approach to life. Anyone who has experienced Integral Deep Listening (IDL) interviewing knows first-hand just how powerful and important the ability to access a variety of different perspectives is for healing, balancing, and transformation. The problem is that most people at this point in time in human development are stuck in just one perspective, or world view, that of their waking identity. That’s a problem. Why?

Quoting Ken Wilber in Integral Spirituality (p. 107), “…a person can have a profound peak, religious, spiritual, or meditative experience of, say, a subtle light or causal emptiness, but they will interpret that experience with the only equipment they have, namely, the tools of the stage of development they are at. A person at magic will interpret them magically, a person at mythic will interpret them mythically, a person at pluralistic will interpret them pluralistically, and so on. But a person at mythic will not interpret them pluralistically, because that structure-stage of consciousness has not yet emerged or developed.” What this means is that your stage of development partially determines your world view, and also the breadth your world view partially determines your stage of development. A narrow world view will limit your development; the broader your world view the more support you have for growth. This is why becoming aware of your world view and learning how to expand it is so important.

IDL is a powerful tool for expanding your world view because it constantly exposes you to perspectives that represent world views that transcend and include your own. Despite that fact, IDL is very foreign for many people because it suspends assumptions that most people take for granted. Psychologists want to interpret, the religious want to make moral judgments, the emotional want unquestioned spontaneity, the spiritual don’t want the non-spiritual, New Agers want happy thoughts and quantum everything, the insecure want a soul and karma, scientists and meditators don’t want fantasy, and most people don’t want to think, give up their world view, or work. With so many reasons to dismiss IDL, it’s a wonder it has any students at all.

Your world view isn’t everything, but it’s close. The assumptions that you make about what’s real, why you’re alive, and how you should relate to other people tell who you are, determine who you will be and what sort of a mark you’ll make on the world. Your world view is that important. Most of us are so subjectively embedded and enmeshed in our world view that we have trouble articulating it. We haven’t thought it through; we can’t tell you where it came from or why we chose it. This is because for most of us, we haven’t developed a world view; rather, who we are is an expression of the world views of others that we have internalized. This is true even for those who take pride that they have “rebelled” and formed opinions different from those of their parents, teachers, and communities. Generally, such world views bears a remarkable similarity to those of our peers, implying that rather than figuring out who we are, we have simply substituted one form of mindless groupthink for another. We not only see this in adolescents, but in corporate careerists, true believers, and politicians of all stripes.

While we all change jobs, spouses, friends, and geographical locations, such changes are relatively minor when compared to a shift in our underlying world view. Your world view sets the context in which you see and experience everything. Your reality is conditioned by your world view, and most of us cling to ours as the foundation of our security and our mental stability. Therefore, it is unusual for anyone, even today, to change their world view more than once. Historically, most people never question or outgrow the world view they grew up with. They think like their parents, family, and culture do. Blessed is the person who is not only allowed, but encouraged, to question their world view. This is what education, and university in particular, is supposed to do, and which succeeds in some cases.

However, society does not have a lot to gain by you doing too much questioning. If you do, you may question its legitimacy, which threatens the prevailing social order. Therefore, you will find many tacit and implicit barriers to questioning your current world view, both externally and internally. One example that comes to mind is the role of “independent journalism” in promoting and enforcing the status quo world view. No one has to tell corporate journalists that if they take certain “third rail” positions in their writing or reporting, they will be fired. At present, you can, for example, survey the mainstream press for criticism of Israel. Where is it? Why is it absent? Is it because Israel has done no wrong or because of the consequences of reporting same? We have Islamophobia, but Judeophobia? The first makes you someone who fears terrorists; the second an anti-semite. Both Brexit and the US Presidential election of 2016 laid bare the gaping avoidance of the economic struggles of the middle class in the West by the ruling elites of Labor and Tory, Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. and Labor and Tory in the UK. A world view was being promulgated that ignored a primary driver of both voter anger and social stability.

Even those who pride themselves for their independence from the world view they grew up with are often merely reactionary; instead of thoughtfully and carefully considering many possible alternative world views, they simply either embrace the current definition of rebellion (smoke, drink, get tattoos and piercings; endorse Pepsi (Democratic candidates) instead of Coke (Republican candidates) or simply do the opposite of what their culture wants (drop out; take up pursuits that annoy people; go avant-garde with new age, art, or music). Another option is to accept and make one’s own the world view of whomever pays your salary. Almost everyone does this to some extent or another because it is generally a requirement if you want to advance at work. You had better convince your superiors you are “on the team” by thinking and acting like they do. If you go to work for the government, you had better not question the underlying assumptions of your position if you want to keep it. If you are in the army, you will accept and follow the nationalistic, black and white, good guy-bad guy world view that is required, or be severely punished.

The ability of these social, cultural, and financial forces to generate not only conformity, but groupthink is not to be underestimated. As Upton Sinclair famously said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” When we add fear of social ostracism to financial incentives the result is that most people have few genuine opportunities to escape their world view, even if they want to. They must be independently wealthy, supported by parents or society, and in extraordinarily insulated and permissive cultural sub-groups that protect them from the usual pressures. Families, schools, universities and monasteries are supposed to supply such freedom, but each imposes its own world view and enforces conformity with it.

We are extraordinarily fortunate today to have the internet, because for the first time in history we have easy, immediate, and inexpensive access to ideas that constantly challenge our present world view by questioning our assumptions about who we are, what is real, right, and important. The internet presents us with remarkable first hand testimony of alternative realities and amazing possibilities that can change our lives. If you put up an opinion on a blog, prepare to have it challenged, regardless of your education, status, or income. The internet breaks down these traditional insulators and defenders against assaults on our world view. This is the basic reason why the internet is one of the most revolutionary, transformative, and positive developments in human history and why so many established social forces want to censor or control it.

World views are notoriously difficult to change. When confronted by new information, we fit it into our world view. As Thomas Kuhn has shown in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, in order to change a paradigm we must experience strong cognitive dissonance that comes from being confronted with experiences that our current world view just doesn’t explain. For most people, this doesn’t happen. They either ignore the discrepancies or incorporate them into their world view. An excellent example is the continued ability of science to ignore and discount the consistently statistically significant findings that shows that minds can know and alter data and events at a distance. The statistical probability is well under 1%, but it is consistently above chance. Another example is the denial of the failure of austerity economics by many of the brightest minds in economics and business. Somehow, massive inequality and a reduction of buying power by the majority is made better by reducing government spending on common social “goods” when the data shows that it has broadly lowered the quality of life and stifled opportunity. In the realms of relationships and mystical experiences, including near death experiences, people either conclude what they want to believe or what they are afraid is true, in either case validating their world view.

What can be done about this? Transpersonal approaches, notably that of Ken Wilber, building on an idea from Charles Alexander out of the Transcendental Meditation tradition, tend to believe that meditation causes world views to transform and expand. Wilber has said that adults, who normally do not advance much in developmental levels, can move ahead two or more developmental levels with regular, genuine meditation. While this may indeed be the case, our world view is an important determiner of our developmental level, and world views are remarkably resistant to change.

I had a good friend, Mike, an intelligent and generous fellow, who illustrates this point. Mike was a millionaire retired investor who spent his time meditating and going to meditation workshops. He was a lucid dreamer and something of a yogi. He experienced altered states of consciousness of various types and was a long time devotee of Ram Dass, Hanuman, and Ram Dass’ guru, Maharaj-ji. Mike grew up in a family of brokers and investors. His father lost his bakery in the ’40’s and blamed it on Roosevelt and The New Deal because the government appropriated the bakery premises for the war effort. His father and grandfather were very determined economic Republicans, meaning they were against taxes, government intervention, and welfare, but were more or less neutral on social issues. Mike also believed in Reaganomics, the Laffer Curve, and Trickle-Down economics. He did not believe in global warming, seeing it as a way for liberals to justify more governmental regulation and intrusion into private lives; he was against a minimum wage, believing that the market would find its own balance, and if that meant that people were willing to work for less than a living wage, so be it. Essentially a libertarian, Mike was a social Darwinist who believed in predatory capitalism and viewed its subsequent social inequalities as natural and acceptable. As a successful professional gambler (he would find that term misleading and disparaging and saw himself as an “investor”), he had life experiences that divided the world into winners and losers, with no sense of social responsibility for the latter. Despite his serious commitment to “spiritual” practices and constantly rubbing up against the associated liberal/progressive culture, he had no problem with a model that emphasized the maximization of profit. He felt like his financial success, which the liberal and progressive meditators envied, validated his world view. It had worked for him and there was real world data, that is, money in his bank account, to support it. The implication was that it would work for these others too, so they really had no excuse for not having money. In fact, in his last years, Mike was focused on finding a way to teach meditators to trade stocks in order to generate the money that could support a life of meditation retreats. He wanted to turn meditators into gamblers in the financial markets, but in service of spiritual ends.

Mike’s world view at its roots was not changed by years of meditation, as taught by Tibetan lamas, and various other talented and experienced meditators. If his world view remained unchanged, how much less likely is it that others, like you and me, who do not meditate four hours a day, or who are not so exposed to radically different world views, will change theirs? The answer is, “Highly unlikely.”

The funny thing is that we all regard ourselves as the unique exception to this rule. Other people may be sleepwalking, lost in the delusional dreams of groupthink, but not me. “I am free. I know who I am; I have a well-thought out world view. I only believe like some others because I choose to surround myself with similar minds; I am not a victim of groupthink.” The question that arises then is, “If you were a victim of groupthink, how would you know?”

What looks like a change in world view is generally far less than it at first may appear. Most people think they have changed their world view when they have changed some part of it. For example, when you discover the opposite sex in your adolescence, find Jesus, meet a genuine psychic, have a great teacher in college, learn a new profession, or have a mystical experience, your world view can change radically. But on closer examination, the change is partial or temporary. Only part of your world view changes or else you have a temporary change of your entire world view. Typically, you enjoy an altered state for minutes, hours, days, or months before crash-landing back into the same old same old. This is typically what is experienced when we take vacations or meet a new love. A permanent change of your world view is much less likely. Why?

To change your world view, you first have to be significantly uncomfortable with the one you have, not just with some part of it. For example, most adolescents are not rebelling against the way they were raised and the sense of self associated with it so much as against some particular restraints on their freedom or particular abusive behaviors of their parents. Secondly, you have to be open to the possibility that there are other, more encompassing world views. While most people will tell you that they are open in such a way, they rarely are aware of the adaptational price they will pay if they do change their world view. The truth for most of us is that entertaining and adopting a revolutionary world view is profoundly threatening. Third, you have to be exposed for an extended period of time to a genuinely transformative alternative world view. How likely is this? How often do people choose to do so? Fourth, you have to be personally secure enough to deal with the threat that a new world view always poses to the assumptions on which you have built your life. Fifth, you have to be in a culture of friends, associates, and influences that are supportive of your change, or at least are not opposed to it. How likely is this, short of joining a commune, utopian community, or monastery? Sixth, this change in world view has to be a lasting change, or else you have a temporary opening, like a love affair, a near death experience, drug high, or religious conversion experience, and simply snap back into your habitual world view. Mike, for example, while open to the possibility that there are other, more encompassing world views and exposed to several, was not unhappy with the one he had, nor was he personally secure enough to deal with the threat that a new world view would pose to some of the basic assumptions of the culture of his childhood. So while Mike fulfilled some of the above conditions for adopting a new world view, he didn’t want or accept all of them.

How often does anyone find themselves in circumstances that fulfill all these criteria? Generally if it happens, it is either by accident or because of good luck, because our waking sense of who we are is generally a fierce defender of the status quo. We think our world view is better than all the alternatives, or we would change. The major exception to this involves career. Education can change our world view, and then the groupthink customary for the profession that we pursue validates that world view. For example, studies have shown that economics majors tend to value profit over human welfare. It is unknown whether this is because such people are attracted to economics or because this is the emphasis of both economic professors and textbooks. However, it is safe to say that while some students already have such a world view, for others the groupthink associated with that professional specialization, combined with the prevailing value system of corporations, strengthens, validates, and demands the adoption of that world view. Therefore, one fairly dependable way of changing your world view is to choose a profession. If you do not already have that world view, consistent emersion in the groupthink of your employers and peers will almost guarantee that you will adopt it.

An Autobiographical Account of How World Views Can Change

If there is anything special about my life that can benefit others, it probably comes from the fact that my world view has been overturned not once, not twice, but three times in profound ways. Each time my world view has been transformed, the result has transcended and included my previous world view. Each change set the conditions and provided the foundation for the next change in my world view. In retrospect, I think this is why it has often been difficult for me to bridge where I am to others: there are a number of intermediate transitional steps that a person needs to have taken or be willing to take for another world view to make sense to them or to have any relevance at all. This is because we invariably assess information in terms of our world view. For Freud, a personal level rationalist, all higher level phenomena, such as mystical experiences, could only be outbreaks of pre-personal, pre-rational regressive delusion. For Jung, a late-personal pluralist and egalitarian, all lower level phenomena, such as schizophrenia, tended to be interpreted as mythic and symbolic expressions of the sacred. Similarly, New Agers tend to either view IDL as a spiritual discipline or dismiss it as a rational dismissal of the spiritual. Scientific humanists, including most therapists, tend to pigeon-hole IDL as Gestalt role-play or simply as telling ourselves what we want to hear and what we already know. True Believers find too many areas that do not match their world view, and so feel threatened.

Everybody has a ground zero world view, the one that they grew up in, that they were scripted to believe by their family, society, and culture. As most people do not learn from their personal history, they spend their lives repeating it. They remain stuck in the world view unconsciously assimilated in their childhood and youth – their religious, culinary, national, racial, friend, and recreational preferences. The pervasiveness of the influence of the world view of our childhood on the formation of our identity, who we believe we are, is so fundamental to how we see others, life, and ourselves that IDL grounds the first module of healing in its educational curriculum in surfacing, questioning, and modifying the assumptions of our scripting.

In that regard, IDL is similar to both traditional and transpersonal therapies, which spend most of their time and energy uncovering and reframing assumptions of that basic life script that still haunt us years after we have left our family of origin. Mine was typical, at least for middle American society. I had grown up as a loved, introverted, fairly spoiled child of “Ozzie and Harriet” ’50’s reality. I don’t remember once seeing my mother or father scared, and anger was a very rare thing. I only remember seeing my father sad once, when I was in my twenties. My parents were both natural optimists and positive thinkers. They were true children of the “think positive,” “your thoughts create your reality” world of the Fillmores, Ernest Holmes, Norman Vincent Peale, and all the “New Thought” advocates of the first half of the twentieth century. They were also Christians, although not particularly devout ones. Every evening at the dinner table, my father would recite the following prayer: “Heavenly Father, we thank Thee for these and all our other blessings. Forgive us our sins and save us. We ask in Christ’s name. Amen.” As a result of growing up scripted into the world view of my parents, culture, and society, it was both my reality and identity. I never recognized, named, or questioned it, nor was that a good idea if I wanted to form a healthy identity. We all have to adopt the prevailing world view of our family and childhood environment in order to gain the acceptance, approval, and self-control that is a pre-requisite to developing a normal, healthy “ego.” And this has been an assumed objective of almost all schools of therapy that I have ever been taught. But what if Krishnamurti is correct when he states, “It is no measure of health to be well-adjusted to a profoundly sick society?”

Let me give you an example. I have never had many problems with anger or sadness, but I have had plenty of problems with other people who grew up surrounded by anger or sadness and had no problems expressing them. I never experienced dealing with such people as a child. I never experienced or had to cope with anyone who had a serious addiction or trauma when I was a child either. I felt loved unconditionally by my mother, my father, my two sisters, and Sadie, the black maid who was a surrogate mother to me. To this day, when I see a black woman, I have feelings of nurturance and warmth. Still, I was not particularly gifted and was self-critical. I was not good at sports, got my feelings hurt easily, was emotionally reactive, and felt a lot of guilt. I was lazy, an undisciplined student, and my inability to do math was a thorn in my side throughout my school years. I did not fit in and didn’t know how to. The worst part of all that was that I thought I was the only one with such problems! I didn’t realize that everybody else was experiencing most of these things too. Such is the nature of childhood narcissism, grandiosity, and personalization.

I did not particularly like myself, despite growing up in prosperity and security. It became clear to me that making money or having financial security was not a solution to my awkwardness and insecurity. I was going to have to figure out who I was if I was ever going to like myself. It helped that I was intellectually curious and did a lot of reading about history and animals. The Bible stories in the Presbyterian Sunday school that I attended probably scripted me to be interested in dreams like my namesake, Joseph, who interpreted dreams for Pharaoh. God was loving and Jesus was a loving parent figure.

I had the enormous good fortune of having a mother and father who were open to all things metaphysical, largely because my father’s mother was a fan of Unity, a metaphysical brand of Christianity, and had a large metaphysical library. I grew up with my parents and grandparents having weekly prayer/Ouija board sessions in our living room. There was a belief in life after death and the ability to contact deceased people. While I don’t remember metaphysical ideas being discussed, I grew up in a culture that was quite open to such possibilities. I had no idea what an extraordinary circumstance that was in America in the 1950’s, particularly since my father had a professional mainstream education, first as a dentist and then as an orthodontist. My parent’s willingness to be open to new ideas was a great advantage, in that it made me view the world and its meanings in a broad way. Still, it was a disadvantage because my friends didn’t share these experiences and didn’t know what I was talking about. That aspect of my scripting added to my social awkwardness and inability to “fit in.”

In retrospect, because I wanted to be liked, I tried too hard to be nice and came across as superficial and phony. Because I was afraid of failure, I didn’t take many risks. I didn’t ask many questions in class, I didn’t challenge my peers, I didn’t go out for sports. I kept my head down. It was probably the biggest mistake in my life. If I had it to do over, I would be a big risk taker, pester teachers with questions, show a lot more interest in others, fail a lot more, learn from my mistakes, and try again. Also, I would know that it takes hard work to be good at anything and be much more determined and persistent.

Basically, my childhood world view was that if something went wrong it was probably something I did or said. Carl Jung would call this being introverted. I would later learn that it is also called having an “internal locus of control.” The advantage of this perspective is that you take responsibility for what happens to you. The disadvantage is that you take responsibility for far too much – you personalize things that people do or say or that happen in the world that have nothing to do with you. I now view taking responsibility for everything in an entirely different way, as narcissistic and grandiose.

The three world views or perspectives that sequentially transformed this childhood world view were those of the Edgar Cayce readings, Nagarjuna’s Buddhist Mahayana Madhyamika, and that provided by many, many perspectives of dream characters and the personification of various life issues of others and myself that I have interviewed over decades. Other major influences were my encounter with Transactional Analysis, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and the integral approach of Ken Wilber.

My first, “New Age” shift in world view

My world view was overturned for the first time when I was thirteen, in 1963, when I was plunged into the world view of the Edgar Cayce readings for five weeks while on a trip to the Middle East with Hugh Lynn Cayce, the son of Edgar Cayce, and about forty-five New Age intellectuals, most of whom were professionals, like Ida Rolf, the founder of Rolfing, and Bill and Gladys McGarey, founders of the ARE Medical Clinic in Phoenix Arizona and the American Holistic Medical Association. There was a man that gave “readings” on that trip, similar to what Edgar Cayce had done. There was also a Texan who claimed to have successfully dowsed oil wells and made a lot of money. A ten-year old girl on the trip could accurately read my mind, which was pretty embarrassing for an adolescent boy! In addition to interviewing faith healers and people who remembered past lives, we meditated together as a group every morning and discussed our dreams over breakfast.

This five week immersion in a holistic, psychic but professional culture was followed in my adolescence by much reading of books about Cayce’s trance readings and my attendance of many ARE workshops in Virginia Beach, Virginia, Texas, and Kansas City, Missouri. All of this taught me a number of core principles that became part of my world view. The first was that the healer or physician, that we need and which knows best what we need, is within, and that we can access it through our dreams. This was an inner, divine intelligence that heals and guides us. A famous core principle of the world view of the Cayce psychic readings is, “Spirit is the life, mind is the builder, the physical is the result.”

The Cayce world view also taught me that dreams preview life events. Because dreams deal with repetitive patterns, they are indeed predictive, and this predictiveness can be and sometimes is precognitive. At the age of thirteen or fourteen I decided that by looking at my dreams I might be able to find out what career path to follow or how to avoid problems that would arise in my life. Another assumption that I learned and accepted was that from the perspective of spirit, there is no death. Yet another was a belief in reincarnation. Your present circumstances are largely conditioned by choices made in past lives. While one can learn a lot about themselves by studying who they have been, both in formative years and in past lives, I learned from the readings and Hugh Lynn Cayce that my focus needed to be on who I was now and where I want to become, not on who I was in some past life. It also taught me that the universe is a loving, supportive place and that my destiny, as that of all people, is to become one with the divine. Central to the readings was the concept of “Christ Consciousness” as an ideal to strive for, and Jesus as the example to follow. It also taught me that the purpose of life was to be of service to others. Regarding meditation, it taught me the importance of a daily practice and a devotional, “I-Thou” approach to transcending my thoughts with a loving, prayerful heart.

After absorbing these concepts throughout my adolescence I could never go back to a sectarian conception of God, sin or the idea of a personal savior. I was now a believer in precognition, medical clairvoyance, astral travel, karma, reincarnation, and the ability of the mind to create reality. In other words, I became a committed New Ager from the age of thirteen, in 1963, before the term became commonly used.

The consequence of my immersion in the Cayce world view during my adolescence was that I did not have much in common with my peers. I wasn’t comfortable around most of them and the friends I had liked me as a person but didn’t understand who I was. When they did start to perceive the genuine differences, they faded away, because our lives were based on different assumptions. I did not have a group of like-minded thinkers around me in the years from 1963 to 1969, with the exception of my family and friends I made at ARE conferences and camp. This was a lonely time for me, but I was filled with the conviction that I was on the right track, because I had felt so validated by the many smart and successful professionals I had met through the ARE. My adoption of this world view was not the result of rebellion against anything or a forced immersion; it was a slow, self-initiated pursuit in an entirely different mental-emotional culture, based on very different premises, but one that was a natural extension from some of the possibilities of my childhood. It was an exciting, different escape from a “normalcy” in which I felt awkward and unable to compete, into a magical world where I could feel special and in control. In retrospect, if I were to do it again based on what I know now, I would have faced my fears and openly asked for the opinions of others about my ideas and assumptions.

My second, Buddhist, shift in world view

I have known many people who have made the shift I just described. It has been a common cultural broadening of world view for people of my generation; I just didn’t know it at the time because mine preceded most of the other similar shifts in world view that I later encountered. I now know that many people were undergoing a similar shift at about the same time. Starting in the late’70’s and increasingly in the ’80’s and ’90’s I found myself surrounded with entire cultures that embraced many portions of this world view, which I would now summarize as “New Age.” However, I already began leaving it in college, when I experienced the second major transformation in my world view. It occurred when I was nineteen, during my sophomore and junior years in college at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, in 1969-70.

I studied philosophy, psychology, and comparative religion in college, rather than pursue some “practical” course of study, because I was very clear that I needed to understand the world views of the wisest people who had ever lived if I wanted a firm foundation for whatever I did with my life. To me this was very practical; from the point of view of making money in the world, it was not. I did not experience myself as an intellectual, although I know now I very much was. I was not much of a conversationalist – I did not talk much about these concepts with others, nor did I seek out others to discuss or debate these ideas with. I lacked confidence in myself and in my ability to express these ideas clearly to others. For the most part, this was a dialogue between myself, books, and teachers, except when I actually taught these concepts in seminars, or classes, or refined them through meditation. In my studies of comparative religion I encountered the world views of Hinduism and Buddhism, and in particular the world view of the great Mahayana Buddhist mystic and philosopher of India in the 3rd century AD, Nagarjuna. What I learned about Hinduism put the world view of the Cayce readings in a broader perspective for me. I now saw it as a form of Christian Vedanta with a large hunk of Blavatsky and subsequent related occult schools thrown in: a belief system that made sense once you bought into its basic assumptions. Advaita Vedanta is the metaphysical position developed by the Indian philosopher and mystic Shankara who taught the unity of Atman (the eternal soul) and Brahman (God).

I still had no doubt that Cayce was an extraordinary medical clairvoyant and that the loving heart of the readings raised the level of awakening of just about anyone that came in contact with any part of them. However, once I was able to get outside that world view and put it into the broader context of advaita vedanta, humanism, theosophy, and the New Thought zeitgeist that was being born at the time Cayce started giving his readings, I saw that many parts of the readings were conditioned by the assumptions of the cultural context in which they were embedded. The Cayce Readings shared the same basic world view as most things New Age, so in contextualizing or objectifying the Cayce material by adopting the Buddhist world view I was also no longer embedded in most of the beliefs common to New Agers.

From my perspective, most people associated with the Edgar Cayce readings, as well as most New Agers, did not “get” the full implications of the Buddhist world view. They attempted to integrate Buddhism into their world view by convincing themselves that Buddhism really was theistic, or because it believed in reincarnation and souls, that functionally it believed in a Self (Atman in Hinduism) that was One with the divine. What happened for me was different. I asked, “What if I take the Buddhist claims of difference at face value? What do they imply?”

The result for me was a transformative world view that was not deistic or theistic or built around the concept of an eternal self. To get there I had to suspend disbelief and consider what it meant to say everything was impermanent, including the self, and that consequently, there are no such things as real “things,” in the sense of lasting, permanent substances or beings. I did not become a Buddhist, but I did subscribe to a number of basic Buddhist teachings. I agreed that everything was impermanent. I agreed that everything was interdependent in its existence and that therefore there were no individually existing beings, only things that appear to be so, but which, on closer examination, are not. This included the concepts of soul and God. I agreed with the Buddhist teaching that what we call soul or self is comprised of five categories of experience: form or matter, sensation or feeling, perception or cognition, volition or intention, and consciousness itself. These are all interdependent, and when they dissipate, there is no more self-sense. I accepted the ideas that there is no permanent, absolute, or real anything, including an eternal soul or a permanent, unchanging God. I accepted these ideas because they made sense, and I didn’t want to base my life on a belief system that was irrational. I knew that if I was ever going to get to a belief system or life perspective that was trans-rational, it would have to be built on beliefs that were rational. The idea of the interdependence of all things seemed to me to be much more satisfactory than the idea of a dying-resurrecting savior god.

In addition, the direct experience of sunyata, or emptiness, in meditation, was very important for me at that time. From Nagarjuna I learned how to silence my thoughts with his four-fold negation. The result, when put into practice, were states of mental clarity I had never experienced before. Here is how the four-fold negation works.

Ask yourself, now, the following questions:

“Am I my body?”

The answer is, “No. I can observe my body, so I am not just my body. I am also my feelings and my thoughts.”

Am I not my body?

The answer is, “No, my body is an undeniable part of who I am right now.”

Am I both my body and not my body?

The answer is, “No. I cannot be both my body and not be my body at the same time.” (Because there cannot be both something and not that same thing at the same time.)

Am I neither my body nor the absence of my body?

The answer is, “No. I cannot be neither something nor its opposite.” (Because there cannot be neither something nor its opposite at the same time.)

This is a process of analytic reasoning about your experience that you can do with any feeling, thought, or concept, such as causation, as Nagarjuna did. If you do so, you will thoroughly, completely demolish any rational reason to believe anything, to feel anything, or to do anything. However, you will as thoroughly, completely demolish any rational reason not to believe, feel, or do anything. The result is not nihilism, but a shifting of your brain into a neutral or “formless” reality. You aren’t A. You aren’t the absence of A. You aren’t both A and its absence. You aren’t neither A nor its absence. A doesn’t exist; neither does non-A. Both A and non-A do not exist and neither do A nor non-A. This is Nagarjuna’s interpretation and the application of “the Middle Way,” the central principle of Buddhism, not just to meditation but to understanding the nature of experience.

If you practice this four-fold negation with whatever comes up into your awareness, whether or not you are meditating, you may find your mind shifting into what Nagarjuna called sunyata, or “emptiness,” which is a state without own being, bhava, (a sense of self or identity) and of complete interdependence. I practiced doing this in my university years and it revolutionized my experience of the world.

The process I just described undercuts belief in Magic Pony Dust, the sparkles you put on your Magic Pony to make it fly. This is because this practice of Nagarjuna’s fourfold negation was not about belief, but about rational analysis of experience in a way that I later learned was phenomenological. It kicks the baby bird of awareness out of its nest of scripted assumptions, causing it to learn that it can fly, or live without them. It now seemed to me that anything that can’t get through Nagarjuna’s middle way, through the eye of this needle, isn’t real and won’t last. I concluded with Gautama that if I based my life on things that I thought are real and permanent but are not (think relationships, financial security, health, and mystical experiences), I would experience pain and suffering when they one day vanish. I saw this very, very clearly, because I had an amazing, astounding professor of Indian philosophy in Fredrick J Streng. He had written his PhD thesis on the relationship between Nagarjuna’s four-fold negation and the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. I discovered that not only do most people not grasp this concept, of a clear space within and between their thoughts and feelings, they don’t want to and have no interest in doing so. It was not so much a belief system as an injunctive reality – a world view that exposed itself through what one did, not what one thought.

By this time I had been teaching both dream interpretation and meditation for two or three years to small groups of people involved with the Edgar Cayce readings. I found that most of what passed for meditation was something else: prayer, affirmations, positive thinking, visualization, mindless repetition, or zoning out in some type of trance state. It became very clear to me that calling these things meditation and teaching them as forms of meditation was a disservice because it merely confused and misled people. At the same time, I did not agree with the extreme position of Zen, which viewed all of these things as Makyo, or useless delusions, to be discarded. I saw them as important aids, just not helpful tools for teaching meditation. Yet my opinion was clearly in the minority, and neither accepted nor understood by the meditation practitioners I knew. All of this caused me to live in the world of ideas and mystical experiences, a world most people dismissed as impractical if they had either the time or inclination to consider it at all, which few had.

Neither Cayce nor Nagarjuna gave me confidence or got me past introversion, self-criticism, self-doubt, and guilt. In retrospect, it is fair to say that a lot of my introspection was out of fear of going out; I could be safe and feel secure working in these inner dimensions; outside it was a wild and scary world with a lot of rejection and failure that I didn’t know how to deal with. Also it fed a lot of narcissistic specialness; I could feel I was unique, even “better,” because I knew all this shit others didn’t. Now it’s amusing to me to look at how narcissistically self-absorbed I was. I still had a lot of that profile into my early and mid-twenties.

I had rational, intellectual reasons why the Cayce/New Age world view no longer worked for me, and I also had an experiential grounding in a broader world view than what I had accessed through my previous one, due to my meditation experiences of formlessness. While the Cayce/New Age world view emphasized a devotional I-Thou relationship with the divine, an approach that is associated with saintly mysticism, Buddhism accessed formless or sage mysticism and the non-dual, or integration of the secular and the sacred in ways that I had not learned or experienced from Cayce/New Age. Because my network of friends from the ARE were either not familiar with the Buddhist world view or were basically new age Vedantists of one stripe or another, I drifted away from the A.R.E. Both Cayce and New-Age oriented people I encountered because they tended to experience Buddhism and formless meditation as life-denying, nihilistic, passive, and self-centered. My basic assumptions about life were now different, although I still shared with my Cayce compatriots a core belief that the universe is loving and supportive and that our destiny was to become one with it. We also continued to share a common belief that the healer is within, and at this point I was still a strong believer in positive thinking, souls, life after death, and reincarnation.

At the time of this writing, many people, particularly those in the integral world, have experienced and adopted some version of the Buddhist world view. They may have entered it through Alan Watts and Suzuki, or Zen, the Theravadin teachings of Vipassana meditation by the Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, the Dalai Lama and Tibetan Buddhism, or Ken Wilber’s integral philosophy, psychology, and spirituality. These people often combine Buddhist meditation, Buddhist philosophy, and New Age energy medicine and quantum everything. This Buddhist and formless perspective was the third major world view that eventually became contextualized, meaning that it was absorbed into a world view that included yet transcended it. That happened beginning when I was about thirty and discovered Dream Sociometry.

Immersion in the world view of Eric Berne’s Transactional Analysis in my mid-twenties was also very important for me. It slowly leveraged me out of the majority of my self-criticism, guilt, personalization, and self-absorption. It did this by my adoption of its choice-based approach to health and growth: the idea that you get to choose what you feel, what you think, and who you think you are. In order to do that you have to make different decisions than the ones that you have been scripted into from your youth. I found this approach liberating, and in my subsequent years as a therapist, I found it beneficial for many people. It changed me from a psychodynamically-rooted therapist in the tradition of Freud’s psychoanalysis, Jung’s analytic psychology and Carl Roger’s “client-centered” therapy to a choice-based, solution-focused approach. While I was never much of a hand-holder, Transactional Analysis made me into more of a short-term therapist, encouraging people to look at the choices that they had made. helping them to make healthier ones, and then helping them to follow through in their daily lives. This is not a particularly warm and fuzzy approach, and I could probably helped more people over the years as a therapist if I had adopted approaches that encouraged shadow work, “reparenting,” and supporting the wounded child.

Part of the problem was that I was a natural believer in asking questions. Taking a course in logic in college reinforced that, as did the study of philosophy in general. As apparently was the case for Socrates, I found that many people took questions about their feelings, motives, or reasons to be threatening. Instead of being happy to have the opportunity to think through their assumptions, they felt attacked. Why? Most people identify with their feelings and thoughts; they are their feelings and thoughts. Therefore, if you question their assumptions, how they feel or why they think what they do, they may very well feel attacked. What this does is make any conversation of any depth taboo because it is too threatening. The result is that many people live rather superficial lives, surrounded by people who rearrange their own prejudices and call it thinking, who move from one drama to another and call it living. Therapies that emphasize a return to “normalcy,” can encourage this escape from freedom, because what is “normalcy” but a pathologically dysfunctional state of delusional groupthink? If you doubt the truth of this statement, look back on your own life. You can clearly see that much of what you assumed was true at the age of ten is now more accurately seen as immersion in groupthink. If that is so, how are you likely to view your current level of understanding twenty years from now?

My third, IDL, shift in world view

My third transformative world view began when I was thirty. It could not have happened if I had not been by nature an eclectic thinker that had not already explored so many different approaches to philosophy, religion, and psychology. I had taken training in both hypnotherapy and Gestalt and found them both too directive. I found the great majority of dreamwork projective: people were projecting meanings, often symbolic ones, onto dreams and other people. I did not feel wise enough to make such interpretations, nor did I particularly care for the guessing game of trying on interpretations until there was an “aha!” experience, which was assumed to be a sign one understood the dream. I was very wary of the need of others to give their power away to parent figures, like professionals like myself, and how seductive and corrupting that power could be for those authorities. A psychic had once told me a story – I don’t know if I can give it any more credence than that – that both identified and then attempted to explain the origins of this attitude I had. He said that I had been a fire-and-brimstone preacher in 1800’s America but had come across an early English translation of Hindu scriptures. I had been so taken by the concept of reincarnation that I started preaching it from the pulpit. The result was that I was tarred and feathered and carried out of town on a rail! This experience had so humiliated me that I was compensating for it this time around, swinging far to the other extreme of not wanting to be an authority to anyone about anything. Whatever the truth of this story, it is true that I was searching for a non-interpretive, non-authoritative approach that would allow people to find their own truth and their own path forward.

By this time I had finished my clinical training in social work, which provided me with a recognized professional foundation for making a living, counseling any population of my choice and getting paid for it by insurance companies. As far as I was concerned, my professional credibility was validated by that training and already by four years of professional experience in community mental health in-patient, out-patient, and day treatment settings functioning as both an administrator and an individual and group therapist. An opportunity for additional education arose while I was setting up and administering pain treatment programs for a community mental health center in northeastern Arkansas, in 1979 and 1980. I put together a health-risk assessment and reduction program for seniors, which focused on improvements in exercise, diet, smoking, and stress-reduction. I found an institution that would accept this work, as well as my interdisciplinary work in developing pain treatment management programs, toward a Ph.D. This was through Columbia Pacific University, a non-traditional and non-certified program in California, that allowed people to submit proposals for projects, life experiences, and studies that would lead to a degree. There were cheaper and easier ways one could have gotten, and still could get, a PhD if they were simply after the title. I knew that involving myself with a non-traditional, non-certified degree program would undercut my professional credibility in the eyes of some, but I had confidence in the value of the work I was doing, and still value what I did for that PhD as more valuable and relevant, in terms of actually impacting positively on changing people’s lives for the better, than most PhD programs provide their students. In addition, I did not have a very high opinion of professional credibility, based on the amount of deceit and outright damage I had already seen in my life perpetrated in the name of it. Because of the non-traditional nature of the program, I chose “Wholistic Health Sciences” as the field in which the degree was granted, to clearly indicate that my degree was not traditional. That PhD work was actually in the area of health education and interdisciplinary health care, which are indeed traditional academic specializations.

Professional groups naturally form guilds which, under the banner of protecting the public, attempt to exclude competition. Two notorious cases of this have been the longstanding fights by the AMA to reduce the credibility, and therefore the financial competition, of osteopaths and chiropractors. In this context, some years later, Columbia Pacific University was shut down as a “diploma mill” by the state of California due to pressure from accredited schools. However, I am still of two minds regarding my PhD. If I had to do it over again, I would have still gotten that certification, which I am proud of, and I would have also gotten a second PhD from Saybrook, where my friend and co-author Stanley Krippner was academic dean. The reason is that reputation and credibility in the eyes of peers and employers matters. I could have reached more people with my work and conducted research to validate it if I had been affiliated with a university. Long after I am forgotten, Integral Deep Listening, or some version of it, will be evaluated based on how useful it is at improving people’s lives, not on my academic credentials. But part of me does hate the thought that some people have used the fact that I have a non-traditional PhD to question the credibility of the method itself, which stands or falls on its own merits. By doing so, they may only be giving themselves a reason to dismiss perspectives that might threaten their own predispositions and habitual world views.

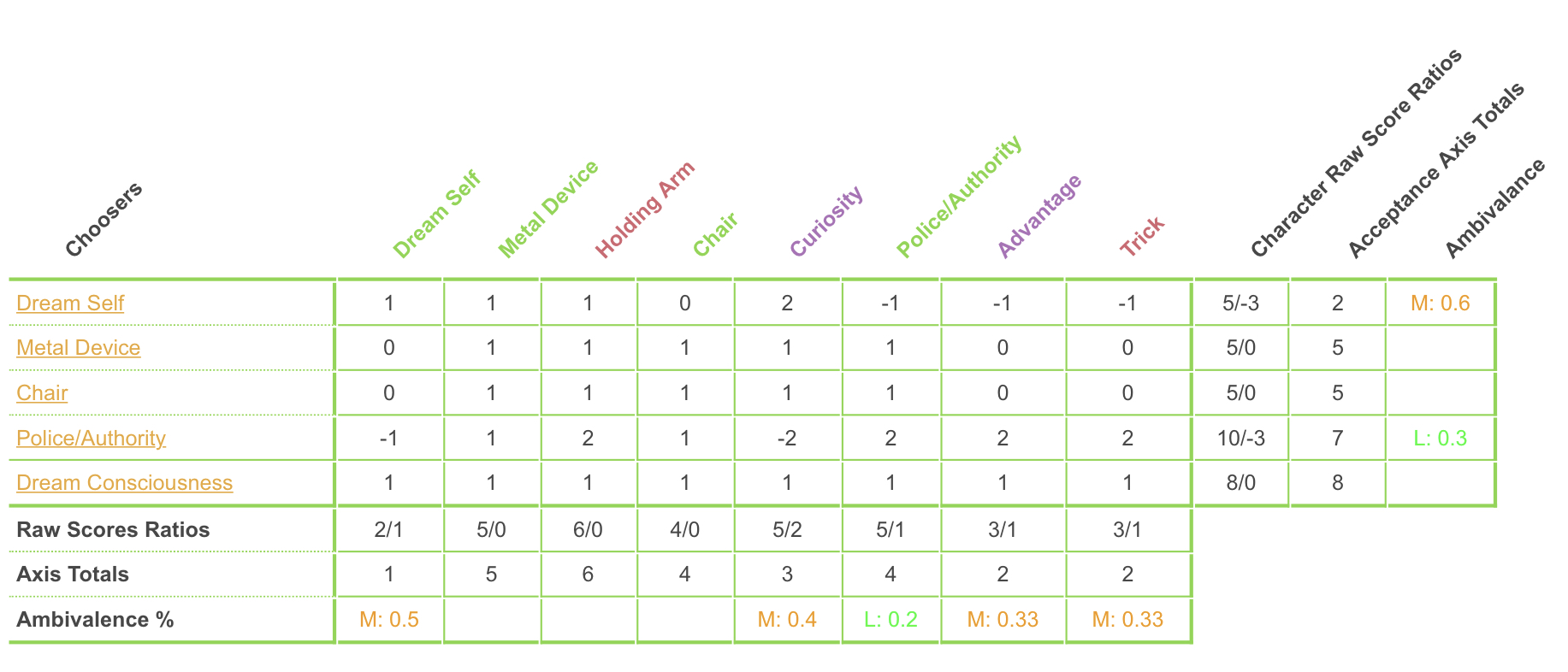

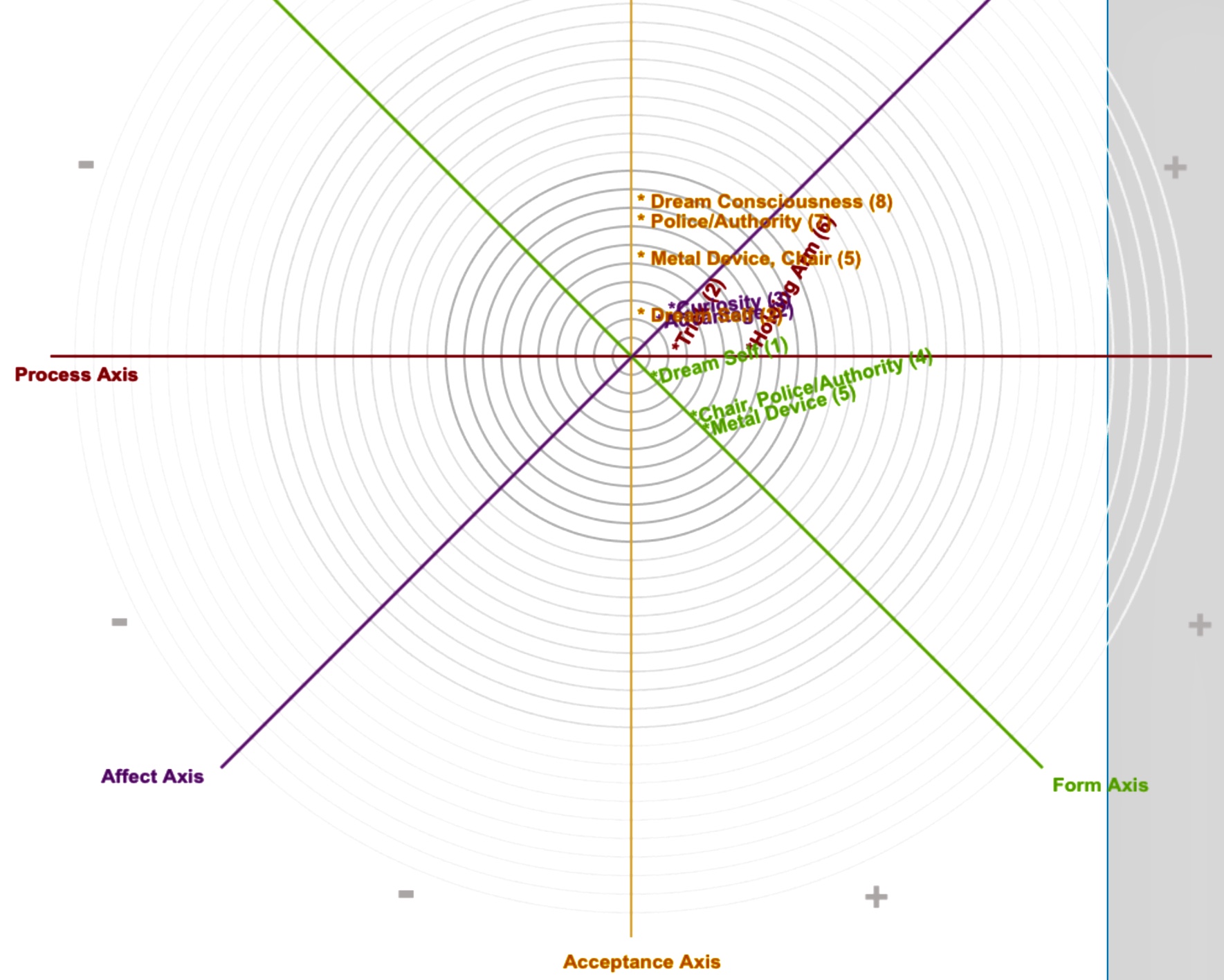

When one of my graduate school teachers, Joe Hart, exposed me to the psychodrama of JL Moreno in 1978-9, I was not so impressed or interested, although I took trainings, including one from Moreno’s wife, Zerka, and learned the method. I also learned a lesser known methodology designed by Moreno, called Sociometry, which was a specialization of Dr. Hart. In sociometry, students or group members are asked to list their preferences regarding some task: “Who would you most like to study math with?” The idea was to take those preferences and use them to reconfigure groups for optimal performance. Some time after I graduated, Dr. Hart asked me if I could write a paper for him on pain management, one of my specializations, and sociometry. I thought for a moment and said, “No, but I can write one on pain management, sociometry and dreaming.” The gears started turning. I asked myself, “What if I treated the characters of a dream as members of a sociometric group?” “What if I became them and figured out some way to collect their preferences?” “Might I not then be able to get an overview of the group’s preferences and perhaps see ways it could be reconfigured to produce a higher degree of collective internal functioning?” I began creating Dream Sociomatrices and Dream Sociograms and becoming the infinite menagerie of dream characters – clouds, spit, dogs, chewing gum, tables, monsters – whatever showed up. Here is an example of a Dream Sociomatrix, followed by its Dream Sociogram:

A Dream Sociogram

Although I had worked with dreams for years from Cayce, Jungian, and Gestalt approaches, the results of this new approach astounded me. I had never come across anything like what I was experiencing. I was amazed by how autonomous these various perspectives were. Their responses and perspectives differed from my own and from those of other characters in the dreams that I “interviewed.” These characters, perspectives or “emerging potentials,” had no problem disagreeing with me and could defend their views in ways which I often found more persuasive than my own. At the same time, contrary to what I had been taught about “ego strength,” all of this identification with different perspectives did not produce any indications of personality fragmentation. On the contrary, the more I became these perspectives, the more they became parts of a more expansive but thinned out “me.” As I suspended my disbelief and became toasters and turnips, I incorporated their perspectives. My sense of who I was slowly thinned as it expanded.

Most of these perspectives accepted me a lot more than I did myself. What was I to make of that? Were they trying to make me feel good? While I was skeptical, I continued the process. Slowly I grew in self-acceptance as I recognized that most of these perspectives just didn’t have any reason not to accept me. This growth in self-acceptance was something that my previous world views and my exposure to many different forms of therapy had not accomplished. Becoming these various perspectives produced a fundamental healing and balancing that was life-changing for me, in a totally unexpected way. I wanted to know why and how this had occurred.

I experimented with this approach for several years with myself and with hundreds of my own dreams to try to understand what was going on and to decide if this process was reliable enough to use with others. All of this research has been collected into two books, Dream Sociometry and Understanding the Dream Sociogram. When I did start using Dream Sociometry with others I found that it was not suitable for all clients or all issues, but there were some for whom it made a huge difference. I found that it was in particular very effective at eliminating nightmares, reducing anxiety, phobias, PTSD, exogenous depressions, providing direct experiences of meditative states, and helping those who wanted to “find their path.” One lady, with chronic agoraphobia and who had tried so many methods she wrote a newsletter on agoraphobia for others, was able to resume a normal social life after some five or six sessions. Another lady, in Israel, who had recurrent flashbacks and PTSD nightmares of a terrorist attack, eliminated her PTSD in one session, just with instructions by email. Another young man, who had been attacked by guard dogs in his workplace, overcame his PTSD in about four sessions. A US Iraq war veteran who had sustained a head injury from an IED explosion, was able to stop yelling at her kids and accept her condition, allowing her to advance with cognitive speech and language therapy.

I also discovered that the personifications of life issues, like the “bolt of lightening” from the metaphor, “it hit me like a bolt of lightening,” the dark cloud hanging over a depressed person, or the “wire” from a stressed out, “wired” person could be interviewed just like dream characters. I came to understand that from the perspectives of these elements there was no difference between night time dreams and waking dramas. I could also interview the tunnel or light from near death experiences. Could this process help keep alive “fire from heaven” even years after mystical and near-death experiences? To find out, I interviewed a number of people who had near death experiences and wrote a book on their interviews with elements from their transformational experiences.

This most recent transformation in my world view was by far the most profound, impactful, and integrative of the changes in world view that I have experienced in my life, for several reasons. It was intrinsic and internal; it didn’t rely on some external belief system like Christianity, Cayce, New Age, Hinduism, or Buddhism. Integral Deep Listening, as I now called the process, was a form of dream yoga that had massive ramifications for our every day, lived waking “dream,” as well as our relationship with and understanding of our night time dreams. The process was a yoga in that it was a transpersonal and sacred discipline or integral life practice. It provided multiple sources of useful objectivity, even though it was, at the same time, highly subjective. It was practical, in that it produced recommendations that I could use to test the method. At the same time, it was not dependent on me or any other authority. Anyone could decide its value for themselves. It produced real changes in people’s lives that could be objectively measured. It could not be outgrown, in that these perspectives presented options that were challenging but appropriate to the current circumstances and level of development of anyone who used it. It was not ideological, in that it did not require belief so much as experimentation. What I and my clients received was continuous access to perspectives that had qualities that were emerging into awareness and that were important for healing, balance, and transformation. Therefore, I called both interviewed dream characters and personifications of life issues “emerging potentials.”

Contributions from Ken Wilber’s Integral

A few years after I first created Dream Sociometry, starting in about 1983. I encountered the AQAL model of Ken Wilber’s integral psychology and spirituality. I immediately saw that his work was exceptional and read everything I could find by him at least twice. I would not say Wilber’s model changed my world view as much as it provided me with a model by which to determine the relative value of world views. Is a world view balanced? How inclusive is it? How transformative is it likely to be? IDL is not based on Wilber’s writings or the integral AQAL model. It grew out of the sociometric methods of JL Moreno, as mentioned above. However, Wilber’s model is the best around today to explain what it means to wake up in a developmental sense. I consider familiarity with his model a pre-requisite for any intelligible conversation about philosophy, psychology, or spirituality, due to its multi-perspectivalism and the extraordinary usefulness of an understanding of holonic quadrants, stages and lines of development. It’s that important. Consequently, I have since attempted to evaluate my own evolving world view, those of others, and those of the perspectives that I interview, in terms of Wilber’s AQAL model. Here are the basic concepts from Wilber’s writings that have been most important to me in developing IDL as a transpersonal dream yoga and form of therapy.

A world view needs to be integral. “Integral” refers to addressing body, mind, transpersonal, and interpersonal life domains. More specifically, it addresses prepersonal, personal, and transpersonal stages of development, various states of being, including waking, sleeping, and dreaming, different levels of development in areas like thinking, empathy, communication, and artistic abilities, and the four quadrants of every situation: interior individual thoughts and feelings that create our consciousness, interior collective values and interpretations that create our culture, external individual behaviors that create our persona or outer personality and life, and our external collective interactions that create our social relationships.

A world view needs to avoid the pre-trans fallacy. Most people think they are more highly evolved than they are. We typically reduce higher stages to our level of understanding or lower because we cannot conceive of higher stages. This is because we haven’t yet attained them, regardless of what states we have experienced. We are confident we have the “right” world view. Prepersonal levels of development are pre-rational, irrational, faith-based, belief based, and generally the product of our familial, social, and cultural scripting. All animals and children are at prepersonal levels of development. This is because a conceptual mastery of language is required to objectify experience enough to witness our body and emotions. Language acquisition is therefore is a pre-requisite to being able to think about our body, feelings, and thinking. Without a conceptual mastery of language we lack the necessary tools to differentiate these aspects of ourselves; we remain subjectively enmeshed and fused with them. To the extent that our adult beliefs are products of our childhood scripting, they are anchored in the pre-personal and are pre-rational. Transpersonal levels of development are trans-rational or arational, and are based on, but transcend and include, clear thinking, logic, objectivity, and rationality. They are empirically repeatable.

The pre-trans fallacy is Wilber’s recognition that it is a perceptual and rational error to reduce transpersonal experiences to prepersonal ones. This is called reductionism. At the same time, it is equally a perceptual and rational error to imagine prepersonal mystical experiences are transpersonal. This is called elevationism. The pre-trans fallacy recognizes that the way these mystical experiences are differentiated is by whether or not they have a rational foundation. If they do not, they are most likely prepersonal and pre-rational, and we only think they must be transpersonal mystical experiences because they so transcend our own identity in experiences of sacred oneness. However, the fact that children and criminals who are at prepersonal levels of development can have mystical experiences is evidence that just because an experience feels and looks transpersonal doesn’t mean that it is. When we make this assumption, we are committing the elevationistic version of Wilber’s pre-trans fallacy.

Integral Deep Listening teaches us not to make this experiential error, and that is important in order to create the internal balance necessary to sustain both healing and transformation.

A world view needs to have some means of verification. Any belief that is based on rationality is at least personal and may be transpersonal. Any belief that is not rational, that is, not based on clear thinking, logic, objectivity, rationality, and is empirically repeatable, is most likely to be prepersonal, regardless of how transpersonal it looks and feels to us. Astrology, tarot, psychic statements that cannot be verified, religious beliefs in the virgin birth, the trinity, the previous incarnations of Buddha, the vision quests of shamans, lucid dreaming, and most types of mystical openings are all prepersonal. Homeopathy is prepersonal, as are beliefs in nationalism, liberty, justice, capitalism, democracy and most economics. Some things like astrology and economics masquerade as personal and rational by using rational methods, but are based on self-validating systems of belief.

The key here, as Wilber lays out in The Eye of Spirit, is empiricism, or the method by which you know what you know. There are three different varieties of empiricism, one for things (science), one for ideas hermeneutics or interpretation and theory), and one for transpersonal experiences (yogas). Each of these share the following three elements: 1) instructions or “injunctions” that say what you have to do (to make a cake, see the rings of Saturn, interpret research results, do literary criticism, or meditate); 2) requirements that you actually perform the experiment, generally under supervision; and 3) verification by experienced peers in the method. The problem with pre-personal forms of knowing is not that they do not reveal truth; they do! It’s not that they cannot be helpful and life-transforming; they are! It is that they do not pass the test of duplicatability by peers in the method. For example, when professional astrologers are asked to construct criteria by which they would have astrology assessed by others, and these measures are used to assess charts by professional standards, there is no consensus. This is the problem with all things pre personal, which are notoriously non-repeatable and non-verifiable. For example, psychic phenomena, such as telepathy, have been shown to occur at a frequency that is above chance, but it is so slightly above chance as to be extremely difficult to duplicate. Therefore, while it exists, it does so in a way that is functionally the same as random chance. Your chances of consciously, predictably creating a psychic experience of your choice at a time of your choice is extremely low. The importance is that empiricism gives us a way to determine whether a sincere belief is transpersonal or prepersonal. For IDL, it provides a way to determine whether an imaginary interviewed perspective is selling delusion or providing a genuine, life-changing transformation.

A world view needs to differentiate between states and stages. We easily assume that because we had a transformational experience that we have attained a higher stage of spiritual development. We are then confused and dismayed when we later find that not much has changed and that we are just as stuck as ever. In fact, life can become both harder and worse thereafter, because we are now much more aware of how stuck we are than we were before the experience. Just because we experience a transformational state does not mean we have attained a transpersonal stage of development. Just because we remember past lives, have lucid or precognitive dreams, or practice meditation does not mean we are at a transpersonal level of development. As noted above, children and criminals can do these things. This confusion and misunderstanding is pervasive in both classical religious traditions and New Age everything. IDL uses this recognition to be able to work with imaginary and subjective experiences, like the personifications of our life issues and dream elements, and to not draw false conclusions about either their meaning, relevance, or reality.

Understanding the AQAL model does not mean that you are transpersonal anything. You can teach the AQAL model to smart children and most adolescents. They can learn it, but that does not mean that they have attained a transpersonal level of development. What it does mean is that they have learned something called “cognitive multi-perspectivalism,” which is the ability to appreciate multiple maps of the same “territory,” whether that is in psychology, art, philosophy, or science. While they will be most fortunate to learn to do so, what they have gained is a heuristic tool by which to understand their experience at whatever level of development that they are at. AQAL is a conceptual model that does not equate to any particular level of development. Consequently, just because I or anyone else understands the model, that does not imply any developmental advantage. Wilber likes to point out that the cognitive line precedes development in the others. This means that understanding integral is a very helpful but insufficient cause for higher levels of development.

Therefore, don’t jump to conclusions about your level of development or that of another person. Just because a person is highly developed in one line (say compassion or cognition) does not mean that they are developed in other lines or at any particular stage of development. Similarly, because a person is an idiot when it comes to mathematics or is a social introvert does not rule out the attainment of some high level of development. The world has recently had a very painful learning experience in this regard. Just because a person is charismatic, a genuinely nice guy, extremely smart, Ivy-league school educated, and a constitutional scholar does not mean that he will function as President at a late personal, pluralistic, egalitarian level of development. What you are most likely to get is a product of the prevailing world view of the power structure in which that individual is embedded. In the case of Barak Obama, that was a late pre-personal culture which is egocentric, narcissistic, and grandiose, built around nationalism, exceptionalism, “indispensability,” and “might makes right.”

All four quadrants need to be considered and balanced in any healthy world view. For integral, all interiors have exteriors and all individuals are parts of collectives. This produces four fields of experience, the individual interior realm of consciousness, states, thoughts, and feelings; the collective interior realm of meanings, interpretations, values, culture, and world views; the individual exterior realm of observable behaviors; and the collective exterior realm of interpersonal relationships, society, social systems, and networks. IDL attempts to take all four into account because if only one of the four lags the others, it stops development to the next level. You need to take into account and nurture all four in order to advance in your level of development.

Contexts determine enlightenment. Culture matters. The broader and more inclusive your cultural context, the greater the possibility of an expansive awakening and higher-order integration. The narrower and self-absorbed your cultural and social environment is, the less likely you are to rise above it. Consequently, take the default position that you are not changing as fast or in ways you want because your perceptual context is too limited in certain key ways that you are blind to. For example, most Westerners are blind to the ways that Russian, Chinese, Iranian, and Moslem societies and culture in general are superior to their own, in some ways. Most people attempt to address this problem by joining some group that immerses them in a culture they believe is positive and transformative. What they usually find is that the belief structure of their chosen group is restrictive. They end up spending their lives living and building someone else’s dream rather than finding and pursuing their own. IDL addresses this issue by accessing subjective sources of objectivity that know you at least as well as you know yourself, yet provide perspectives, and therefore a culture, that transcends your own. These interviewed perspectives see where you are blind and make practical, realistic recommendations for getting unstuck.

Development requires an integral life practice or yoga. An integral life practice is about putting a world view to good use. It can be built around your career (called dharma marga in Hinduism), your relationships, or your physical health. An integral life practice focuses on getting out of your own way, becoming transparent, and waking up. It is therefore a yoga. IDL is a dream yoga in that it views development and awakening as predicated on the clarity of your world view. Its integral life practice is coordinated not by your waking preferences and goals but by a consensus of preferences of interviewed emerging potentials.

In self development, the cognitive line leads; in collective development, the moral line leads. This is not a principle from Integral AQAL but one I came to myself. Most of us don’t question our morality because we know our intentions. We justify what we do based on our intentions, which are generally noble. However, that is not how others judge our morality. They ask, “Does he/she respect me?” “Does she reciprocate?” “Is he trustworthy?” “Is she empathetic?” It is not enough to get concurrence from our fellows who have a vested interest in telling us we are wonderful. What we need to do is to consult various out-groups – members of cultures and groups who have very different experiences and worldviews from our own. How moral do they think we are? By this test, we are confronted by the fact that at present, by and large, humanity is enmeshed in an amoral and exploitive economic system that puts profit before people, and controlled by an immoral political system that is exceptionalistic and enforces its control through “might makes right.” Because we are members of those groups, while we may sail ahead in cognitive, musical, or the line of spiritual intelligence, our overall development is blocked.

This principle is important for recognizing that just because we understand mysticism and mystical states and the transpersonal, that does not mean that we have attained some transpersonal level of development. It also means that because we have moral intentions does not mean that our behavior is moral. Morality is determined by the assessment of objective collectives, not by our intention. In society, the assessment of moral intent is made by social norms and codified law. In our interasocial collectives, our morality is made by the assessments of multiple interviewed perspectives. These serve as important, even vital, subjective sources of objectivity.

Developments in meditation

Around the same time I was researching Wilber’s integral I started observing my breath and noticed that it had six distinct parts, and that each of these involved a different process and quality. These different qualities became the source for self-scoring in confidence, empathy, wisdom, acceptance, inner peace, and ability to witness that is a unique feature of many IDL interviewing protocols. I reasoned, “If these qualities are embedded in our relationship with life in the most intimate and reliable of ways, then they are fundamental characteristics of waking up, or enlightenment. I can use them to find out how awake, enlightened, and balanced in these qualities these different interviewed characters are.” This is called “IDL Pranayama,” and I wrote a book about it.

With IDL anyone can access perspectives that are awake, alive, balanced, detached, free, and clear in ways that they are not. You will become many perspectives that are relatively unscripted, do not do drama, and know how to avoid getting caught up in it. They often will be found to represent perspectives or world views that you have not yet grown into. By listening to them you will defuse interior conflicts that contribute to disease and suffering, while supporting the birth and growth of your potentials. Meditation is high-octane fuel for these perspectives. It provides abstract or generalized objectivity. Integral Deep Listening interviewing provides concrete objectivity regarding the specific life issues that matter the most to you. When you combine Integral Deep Listening and meditation, you are likely to discover growth is speeded up in a profound yet natural way.

Non-reliance on a “self”

Because these interviewed characters exist in a state of neither definite existence nor definite non-existence, it is impossible to give them a definite ontological status. By becoming them you will have multiple experiences of what Buddhists call anatta – the absence of any real self. Consequently, IDL does not find much use for the term “soul,” and it does not emphasize reincarnation, which it views more as dreamlike stories we tell ourselves to validate certain world views. These “stories” can involve inheriting physical wounds from a past life, or having accurate memories of places and relationships from a previous existence. In other worlds, many such stories are “real” and contain “truths.” Still, they remain dreams, only dreamed by a larger sense of identity that still lacks permanence. Direct experiences of the lack of both reality and non-reality of interviewed emerging potentials has not made me more of a Buddhist, but it has validated the idea of “no self.”

This is because as the self becomes more transparent, it loses its value as a source of orientation, a center of meaning and value, and a source of security as you practice taking multiple perspectives. Because identity is as strong, yet arbitrary in a toilet brush as in yourself, your attachment or identification with any stable, permanent sense of who you are recedes. Your sense of who you are is objectified and seen for what it is: a temporary tool, whose sole purpose is as a vehicle through which life can more completely wake up to itself.

Non-reliance on a concept of karma